Lancashire achieved its fame and fortune as the first industrial society and it was achieved not without cost. The cost of riot, arson, class bitterness and hatred but most of all exploitation not only by the employed but also of one class of workers by another.

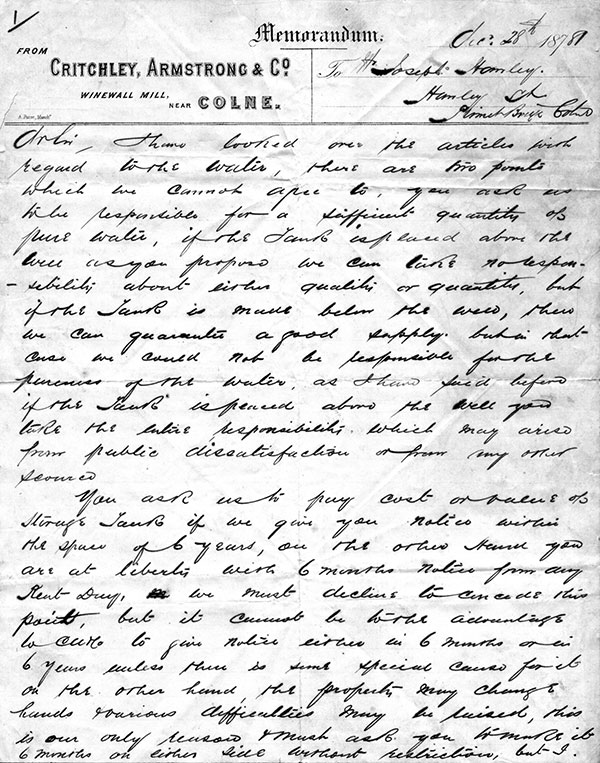

As workers, previously working alone or with families, began to collect together under the new factory system, so they began to realise their collective strength. Even the handloom weavers realising this, began to strengthen their associations at the end of the eighteenth century until the Combinations Acts of 1790 & 1800 outlawed incipient trade unionism and put enormous power into the hands of the masters. That such power was misused by some of them is now too well known to need cataloguing here, suffice it to say that the tales of maltreatment of operatives, in many cases children, in the first half of the eighteenth century make chilling reading. In many cases this was caused by the cut-throat competition in an industry where demand at that time was insufficient for the supply available. The manufacturers, alarmed at the appalling conditions and low wages being paid by some of their number, took the unusual step of writing to William Huskisson, President of the Board of Trade, appealing to him to introduce legislation for a minimum wage. They agreed with the weavers’ statement that:-

“A few unprincipled wretches seem determined to lower wages, so long as there is a shilling to deduct”

And went on to say that these men, by reducing wages below the agreed list had monopolised trade

“To the exclusion of the respectable and humane manufacturers”.

When there was such universal condemnation of the state of affairs improvement had to come. Victorian public opinion’s condemnation of these excesses resulted in the Factory Acts of 1844 and 1853 and the Ten Hour Bill of 1847 with its later amendment concerning the hours children could work. These went a long way to remedying the worst of the abuses.

Meanwhile the workers strength had been growing. In 1824 the Combination Laws, were repealed and from 1840 onwards there is evidence of weavers of different areas getting together to compile “lists”, which were calculations of how much weavers should receive for weaving different types of cloth. There was a Nelson weaving list in operation in 1866 and in 1870 Nelson Weavers Association was formed with an original membership of 400. Strikes began to be used as a weapon of negotiation, there being lengthy ones in 1878 and 1880, and by 1896 the total membership had risen to 4,500.

In the face of this growing organization on the part of the operatives, the manufacturers began to organise themselves and in 1891, on August 5th, Nelson District Manufacturers Association was formed when representatives of the town’s manufacturers met at The Station Hotel dining room and elected William Reed as their first chairman. Originally the object of the association was simply to act as a body representing the employers in their negotiations with the union. Slowly this role evolved and joint procedures and rules were agreed to minimise the effects of any disputes that occurred in the town between employers and employees. After the First World War this role was extended even further to include acting for individual weavers in dispute with their customer where it was felt a matter of principal was involved.

James Nelson’s was not represented at that first meeting in 1891 but joined the Association about six months later and James was elected to the committee in 1894. Between then and 1898 James or Amos were somewhat sporadic attendees of meetings, in 1898 however, James Nelson’s left the Association and did not rejoin until ten years later when it was recorded they had 1203 looms and were the second largest manufacturer in the town.

From this time onwards it was clearly Joe’s job to attend manufacturers meetings although Amos would occasionally go, usually it would seem when Joe was unable to attend. Joe was put straight on to the committee in 1908 and rapidly became involved with the running of the Association. He served on such committees as the one to consider the formation of a list for chain beaming and another in 1919 to raise a fund to commemorate the peace and recommend what to do with the fund.

In 1919 the rules of the Association were changed, possibly at Amos’s instigation. He had been asked to become Chairman and had refused. The Association then decided to reorganize the main activities into three sub committees and only expect the chairman to attend occasionally, although he would be an ex-officio member of all the committees. Amos then agreed to become chairman and with the position came membership of the General Council as one of Nelson’s representatives. He remained Chairman for 5 years until 7 January 1924 when he became President, having been a respected if not particularly active chairman. During these years the Association moved premises and one of the minutes of August 1921 records that “an offer of £1750 be made for the new premise, on condition that there is no restriction whatsoever with regard to the sale of intoxicating liquor”. The President was not present at that meeting but he cannot have objected very strongly as he officiated at the opening ceremony a year or so later.

Joe meanwhile was an assiduous attendee at all committee meetings and those sub committees of which he was a member, gradually assuming more influence and in 1925 becoming Vice Chairman and a member of the Central Committee.

Causes for disputes, which reached the manufacturers association over the years were many and various. In 1913 the overlookers (or tacklers) at one mill were refusing to accept into the union a man the employer had set on as an apprentice, seemingly on the grounds that he was “of very small stature, was 40 years of age, and very deaf”. Of rather more substance was the complaint made some years later by the Cloth Lookers Union regarding the dismissal of one of their members. After what seems to have been a certain amount of prevarication, the manufacturer concerned was forced to admit his only reason for dismissing the man was in order to replace him with his own brother in law. It appears to have been a case where domestic harmony was only achieved at the expenses of industrial confrontation. It was a sign of the times, though, that the Association, after due consideration, seemed to find nothing untoward in the employer’s behaviour and passed a resolution that Mr. Smith could run his business how he pleased. The fact that the union took this matter no further may be explained by the fact that the clothlooker concerned does not appear to have been unduly inconvenienced as he had already found a job as a pianist in Blackpool.

This particular case perhaps gives a slightly unfair idea of their partiality. While, obviously, they tended to take the employers side they were quite prepared to censure those who, broke the agreements. The employers who formed a joint committee to enquire into unrest at one mill with two union men agreed that “the ill will and strained relationships, between employer and employee were largely brought about by the indiscreet acts of the employer”. Some of the most difficult disputes, though, were between different groups of operatives. This was really not surprising when one bears in mind the organisational structure of weaving at this time. Weavers, as I have already mentioned were paid on a list, which meant by the amount they produced. It was therefore important to them that their looms were well maintained and attended to quickly if a fault developed. For this they were dependent upon the overlookers, a somewhat independent group and some would say regarded as the aristocrats of the weaving world. Even if all went well between the weaver and his, or more likely her, overlooker, there was still the hurdle of the clothlooker to overcome. They were unionists like the weavers and overlookers but in a sense had management responsibility in that they could recommend that the weavers were fined for faulty cloth. As any textile man knows, there are as many opinions as to what is a faulty piece of cloth, as there are people inspecting it.

In April 1924 a young male weaver went to find his overlooker as one of his looms was making persistently bad fabric. After much searching the tackler was found examining the manager’s car. Somewhat unwillingly, one gathers, he told the weaver he would be along presently and eventually arrived some 25 minutes later. The weaver, as the contemporary report has it, drew the tackler’s attention to the fact that he had had the loom stopped for this length of time. The tackler then took him by the neck and gave him a shaking. The manager called them together and extracted an apology from one to the other, immediately afterwards another weaver heard the tackler explaining exactly what he would do to the weaver if he complained again. The weavers at the mill called a meeting, held a ballot and voted 100 to 3 to refuse to work with this overlooker in future. This complaint was brought to the manufacturers association, who, in their wisdom, decided the overlooker was undoubtedly at fault but felt that in such hard times to lose his job was rather a severe penalty. They suggested that the overlooker should regard it as a final warning and the weavers return to work on that basis.

Sex occasionally reared its ugly head. The manager of one mill was arraigned before the committee because he had “put his arm round Mrs Sagar a respectable married woman, and tried to entice her into the weft store”. On another occasion the weavers insisted that a tackler should be brought before the committee on the grounds that “he had shown to Miss Bancroft objectionable familiarity which led to the act of indecency by the other tacklers”.

For a student of industrial relations the period we are talking about in Nelson contains examples of almost every form of industrial conflict. These industry wide and local incidents have proved a fertile ground for the study of these problems. Many reasons can be advanced for radicalism of the town. The development of “room and power” in Nelson encouraged the growth of a large number of small firms, and in a period of depression such as existed between the wars these are usually the first to feel the financial pinch. The structure of the industry was different in Nelson to most other weaving towns. The proportion of male weavers was much higher in Nelson for one thing. In Blackburn 90% of weavers were women but in Nelson the higher proportion of male weavers made the wage levels of more importance than where there was already a husband bringing a wage into the family as well as producing a more militant workforce.

The very fact that because of the nature of its trade, Nelson did not suffer the extremes of the depression that affected other parts of Lancashire, meant that the mills were not in such imminent danger of closing down and action by the unions was less likely to be counterproductive. The weavers union was strong and reasonably well financed, the employers too were both well disciplined and adequately financed. Individually too, there was less incentive for even the most militant to agitate where such agitation was likely to close his firm and put him in the dole queue and still less that he could achieve by such action if he was already out of work.

The social structure of the town was more susceptible to radicalism. Nelson was a new town that had grown fast and recently through the cotton boom. There was little of the established social structure based upon more feudal times that might have provided a structure of traditional tolerance, instead the whole hierarchy of the town was based upon the industry, its conflicts and prejudices.

Surprisingly, perhaps, in view of what has just been written, the first large dispute to affect the industry in the twentieth century did not start in Nelson. It was on a subject that seems to have lost none of its topicality over the, intervening years the closed shop.

From 1910 onwards the unions were pursuing their policy of gaining 100% union membership increasingly aggressively. Membership campaigns in these years succeeded in increasing the membership from 137,000 to 197,000 but in 1911 it was decided to try and achieve closed shop arrangements by more militant action at individual firms. The employers made clear their opposition to this from the beginning and a confrontation was inevitable. It occurred in Accrington where an ex union official called Riley and his wife both refused to join the union and their employers refused to sack them for not joining. The weavers struck and the county’s employers declared a lock out insisting that their mills would remain closed until the unions agreed that “ a strike as a measure of coercion against non unionists must, for the future, be impossible”.

As became the case in many of the subsequent conflicts, this was fought with different levels of enthusiasm in different areas and by different districts. In Nelson the struggle was particularly fierce as a rival employees’ body, the Nelson and District Catholic Workers Federation, existed, led by a Catholic priest, Father Robert Smith. It was pledged to fight socialism and secularism and the union’s determination locally to win the closed shop dispute was prompted by its belief that it must crush the Catholic Workers Federation. The union at national level was nothing like as determined and the strike ended after two weeks in an almost total victory for the employers. In Nelson, though, this was by no means the end of the matter. Bitter at being let down by their union, the local weavers pursued the closed shop in even move aggressive fashion. Individual members of the Catholic union were harried by bands of union members, some were surrounded in their homes and confrontations occurred almost daily in one case involving over 1000 weavers, to which the police had to be called. Gradually normality returned, although the underlying rivalry and bitterness continued for many more years. The Catholic union was renamed “The Nelson and District Protection Society” and survived until the twenties when the slump finally achieved what the weavers union could not. Up to that moment, however the weavers union continued to pursue the end of a closed shop. In 1919 the union circularised all its members instructing them to bring their union membership cards to work the following Thursday. Nelson Manufacturers Association heard of this and instructed all their members to make sure that on that day all weavers should be strictly kept to their looms and not allowed to go round visiting other weavers (examining their membership cards). “If a weaver refuses he should be discharged and if a strike occurs following that discharge, a General Meeting will be called at once to consider the situation and the committee will recommend the meeting to pass a resolution for a total lock out in the town”.

As the post war recession hit the industry in the twenties, the causes for dispute became more related to factors that directly affected the operative’s security of employment or level of wage. Of these the most damaging was the custom of “fining”, whereby the weavers had sums of money deducted from their wages if the cloth they produced fell below a stipulated quality level. This practice had been a bone of contention even in the days of the handloom weavers. In the eighteenth century a certain Giles Gee, who had fabric handloom woven for him over a wide area of the county, was reputed to have had a 38” “yard” stick for measuring the pieces. What was fact was that he fined his weavers a shilling for every hole he found. On one occasion, a weaver, who was found to have two small holes in his piece, remonstrated that the fine was unreasonably large. “Its a shilling a hole, big or small” said Gee, whereupon the weaver took out his knife and made the two small holes into a large and long one. “I’ve spoilt your cloth” he observed, “but I’ve saved myself a shilling”. The matter had never been properly settled even during the prosperous times at the end of the previous century and now, with wages dropping and unemployment rife, it led to increased bitterness both between the weavers and the cloth lookers and between weavers and management.

It came to a head in 1928, when J. H. Husband, a weaver and union official, was dismissed by his employers, Mather Bros, and the dispute escalated into a town lock out lasting some six weeks and which involved both Amos and Joe.

Joe at this time was Vice Chairman of the Manufacturers Association and as the dispute was directly concerned with affairs at the Chairman’s mill, Joe in effect acted as chairman and leader of the manufacturers throughout the dispute.

The whole thing started when Husband, a weaver of some 28 years standing, was called up by the clothlooker after the examination of half of his pieces, and warned that the cloth was not good enough. The weaver disagreed with this opinion and said it would pass anywhere. He then returned to his loom and the cloth looker examined the rest of the pieces. He found several more faults; one so bad it would have to be cut out, so he sent for the weaver again and told him this would necessitate a shilling fine. Husband refused to accept the fine, the head clothlooker was called and the whole affair was passed on to Harry Mather one of the directors and the son of the owner. Harry Mather inspected the piece and finding the clothlooker’s verdict correct, in his opinion, interviewed the weaver. In reply to Mather’s question of what he had to say about the piece Husband replied “nothing” When then asked what he had to say about future pieces he was equally unforthcoming. Mather then pressed him further to give an undertaking that in future he would produce better pieces which Husband refused to do. Upon hearing this negative response Harry Mather said there was nothing more for it, he would have to leave. As Husband was going away, Mather asked him to see his father but this he refused to do.

Such were the facts of the case. When the union brought the case to the Manufacturers Association charges and counter charges were brought. The weaver claimed that the clothlooker involved was trying to get his own back for past troubles that Husband had caused him. He also resented the fact that Mr. Harry had lectured him about the piece in front of the other cloth lookers. The cloth lookers, for their part, gave evidence that Mr. Harry had not in any way adopted an aggressive attitude toward the weaver, and further accused Husband of trying to enforce a very low standard of production at the mill. They accused him of undue interference with the cloth lookers and complained that he had threatened, “To have the cloth lookers put in their place”. They stated that “his method of interference on behalf of the other weavers who were being cautioned about faults in weaving and his telling them not to take any notice of the cloth lookers. The sarcastic mannerisms he adopted when engaged in these acts were undermining the management throughout the place. In their opinion, the attitude he adopted to the last piece woven on loom 692 without any provocation, was quite in harmony and in keeping with the attitude he had had on many previous occasions, both on his own and other peoples’ behalf”.

Originally, the employers’ case was that it was Husband’s attitude and his refusal not only to pledge himself to do better work in the future but also to meet the Managing Director to discuss the Matter that earned him the sack. They compromised the case however, by appointing a sub committee to examine the piece and from then on the dispute widened into a conflict on the whole practice of fining and the employers rights in this regard. Before proceeding to that, though, the examination itself lent a touch of farce to the proceedings. The manufacturers sub committee duly examined the piece and, predictably declared that they could come to no other conclusion than that it was faulty. It contained such weavers’ faults as did not warrant the weaver taking up the position he had done all along, The weavers representatives were then given the opportunity to examine the piece and they, equally predictably, declared it a very good piece. The manufacturers, claiming that the light was very bad when the union representatives examined the piece, persuaded them to re examine it by daylight but could not prevail upon them to change their opinion.

After various attempts at negotiation, joint meetings at the Mill and at the central employers federation and the Amalgamated Weavers Association in Manchester had proved abortive, the weavers at Mather Brothers decided to strike and were supported by the union. The manufacturers were quite clear on their position by this time, a strike in support of Husband was a gross interference with the management of the mill and as such must be resisted at whatever cost. They therefore declared a lock out of all the town’s weavers . which commenced on May 29th 1928 . The next morning 51,000 of the town’s 55,000 looms were stopped.

Amos looked on all these events with increasing disquiet. Trade was bad, all the mills were fighting to retain what share of the trade they had, domestically and in the international market against competitors from all over the world. He saw the interruption of supply to their customers, as a catastrophe for all the weavers in the town. As he stated in a contemporary letter

“In most cases, the business people have to be very conservative. For instance, if we have been using a certain spinner’s yarn and we find that he supplies his yarn of a regular and reliably quality, his price is reasonable and he is a man who is reasonable and obliging, we should take a lot of persuasion to change our spinner. On the other hand, if we had to change for any reason, strike or otherwise, and we got into another spinner who was just as good, we should stick to that spinner, so long as we got good treatment. I believe business people, as a whole, work this way. We have a customer at present who has taken our goods for a very considerable time, he will be compelled to buy from other firms. The probabilities are that we shall never get this trade again as we have had in the past, except if he finds the goods or his treatment are not as good as he had from us”.

Amos was not a man to sit quietly by when he felt that things were happening that gravely affected James Nelson’s even when the man at the centre of the lock out decision was his own son. He approached the Mayor of the town with a view to finding a formula that would ensure a return to work while the matters of principle causing such bitterness between the two sides were negotiated in a calmer atmosphere.

As a way of achieving this he offered to employ, having interviewed him privately, Husband at one of James Nelson Mills at wages and conditions at least equal to those he had been receiving at Mathers. The union “while warmly appreciating Sir Amos’s efforts” felt they could not accept this solution as the main principle for which they were fighting involved Husband’s reinstatement by Mathers.

Amos tried again, this time tackling the other matter in dispute. He wrote to the Mayor on June 1st causing him (the mayor) to write as follows to the manufacturers the same day,

Sir Amos Nelson has put a proposal to me today which I think is worthy of your serious consideration. He believes there are two matters upon which your executive and the employees executive should come to an agreement upon before the present dispute can be ended.

The first is the matter of the position of the dismissed employee, the second the question of the future relationship of employers and employees particularly with reference to alleged faulty cloth.

Sir Amos suggests that the two executives might try to settle the second point without prejudice to the first”.

At the meeting of the Nelson and District Employers Association called on June 4th to discuss this letter Joe offered his resignation as acting chairman and from the committee on account of the unofficial correspondence taking place between the senior director of his firm, the Mayor and the Nelson Weavers. This offer was unanimously rejected, and he continued in the chair. At this meeting it was decided that if the union would agree, the manufacturers were willing to leave the whole matter to arbitration by the two central committees. The weavers union replied that it would attend such a meeting.

Upon receipt of this communication the Mayor, the town clerk and Sir Amos met privately. The town clerk made the suggestion that should the negotiations break down over the future of Husband, a compromise solution might be that the weavers union themselves nominate someone to take his place at Mathers and select a firm for him to work at. This still did not satisfy the weavers, who turned it down and the manufacturers side, on June 11th at an extraordinary meeting, at which all but 200 of the looms affected were represented unanimously passed a resolution stating that “the weaver be not reinstated by Mather Brothers”.

Despite all the attempts to stop it the dispute dragged on until July 12th when the weavers abandoned their demand for Husband’s reinstatement. He was found work at James Nelson and a joint committee was set up between the employers and the union to discuss the whole practice of fining. Joe was a member of that committee and a special invitation to Amos to attend is recorded, in the Manufacturer Association’s minutes. While the union agreed to the formation of this joint committee, and in fact two meetings were held, it in no way altered their determination to end fining, at the earliest opportunity. Having failed by direct industrial action they tried other means. H. Ridehalgh and Sons gave them the opportunity they wanted when they fined one of their weavers, Thomas Sagar, one shilling for faulty cloth. The union responded not by conventional means but by taking the company to court. The plaintiff, represented by two famous future Labour politicians, Stafford Cripps and Harold Laski, won the original case in the Chancery Court. The case went to the Appeal Court, and the previous ruling was overturned so that the company won. The union was not satisfied with this judgement and approached the T.U.C. with a view to taking the case to the House of Lords. After taking advice from two K.C.’s however it was decided not to pursue a case which had already incurred court fees, estimated at £40,000.00 trying to recover the original shilling.

It might seem strange that in all this story of conflict there has been no mention of the general strike. It was a time when all the union workers went on strike and all that was possible was for some essential services to be undertaken by the family, the managers and some non-union employees. The only story that has come my way from that difficult time is one concerning Joe’s eldest son Gilbert. One of the things that needed doing was to keep the customers as happy as possible at a time when James Nelson’s was not supplying their cloth and so the managers went round cutting off the half made pieces, loading them on the lorry and Pickles, the mill chauffeur would take them into Manchester. The strikers got wind of this after a day or two and used to hide on Manchester Rd. in Burnley, which was a steep uphill drag, jump out at the steepest point when the lorry was going at its slowest and cut the ropes holding the cloth rolls with the result that they rolled off onto the road. Gilbert then decided to take a hand. He had the pieces loaded in such a way that he could hide among them out of sight. His idea being that he would jump up and with a shooting stocking filled with sand belabour anyone trying to cut the ropes. It was by all accounts a very hot day, the lorry ground its way to Burnley where it stopped and a lengthy conversation took place between the driver and some people standing by. Gilbert was getting hotter and hotter. Eventually he emerged from his hiding place and demanded what was causing the delay. The driver was very apologetic “Oh I’m sorry Mr. Gilbert” he said “quite forgot you were there, I’ve just been told the strike’ s been called off.”