My Grandfather James Nelson, was born in 1831, when Queen Victoria was a girl of 11, but, more appropriately for him, five years after the events of 1826, when the handloom weavers of Lancashire, after years of suffering, had rioted and rampaged through the county, burning down some mills, and forcing entry into others where they broke up the power looms, which they saw as the cause of their distress. Clashes occurred with the army and one Clitheroe mill went to the lengths of building a moat to protect itself in the event of a recurrence of the troubles.

The last half of the eighteenth century had been a prosperous one for Lancashire. The county’s population had increased from 160,000 at the beginning to 695,000 in 1800. The inventions of Hargreaves, Arkwright and Crompton allied to the work of Watt, whose steam engine, was increasingly being developed for industrial purposes, meant that a supply of yarn never previously matched for quantity or price was available to the handloom weaver.

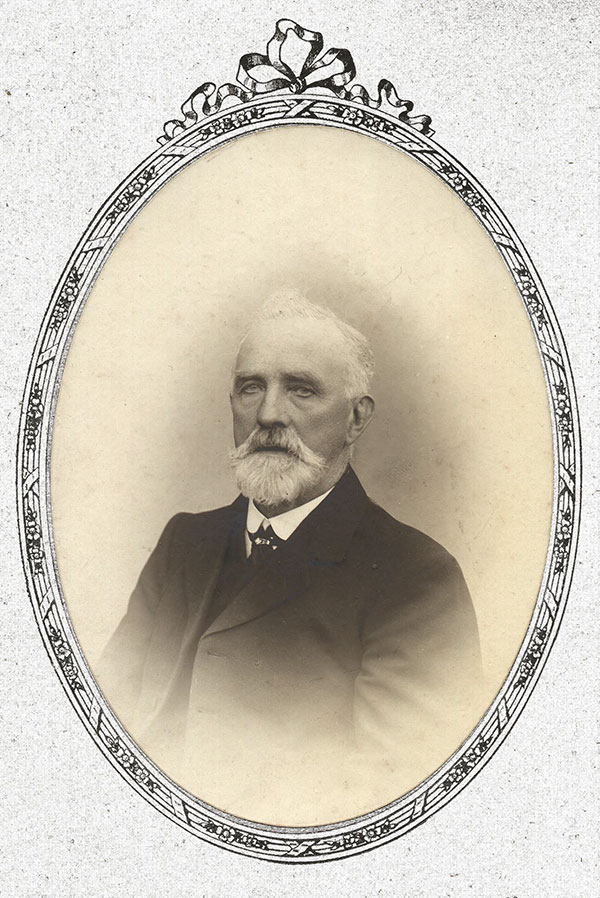

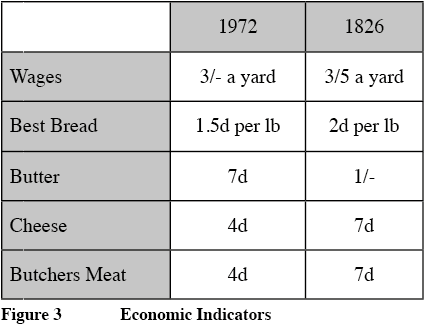

Their export markets expanded and flourished and withall they kept their independence. In 1799 this all changed. War with France cut off their markets, the power loom was taking much of the remaining market, and even peace when it came, did little to alleviate their lot. Some idea of their sufferings can be gathered from the figures produced by the handloom weavers of Bolton in 1826.

The Nelson family had traditionally been hand loom weavers in and around the Colne area. James could remember the days when he would drive with his father from Winewall over the moors to Halifax, sell their pieces of cloth, with just enough time to buy the necessary yarn for their next batch of pieces before driving home. They would leave Winewall at 5 in the morning and arrive back at 10 at night.

By 1842, when it was time for James to start work, there was obviously no future for the handloom weaver. Conditions in the town were somewhat better than they had been 1829, when 1,940 people, one third of the population, had an income of 2d a day. Even if they were better than they had been however, the conditions in 1842 were still dire. W Cooke Taylor who made a tour of the Lancashire manufacturing towns in the summer of that year reported:

By 1842, when it was time for James to start work, there was obviously no future for the handloom weaver. Conditions in the town were somewhat better than they had been 1829, when 1,940 people, one third of the population, had an income of 2d a day. Even if they were better than they had been however, the conditions in 1842 were still dire. W Cooke Taylor who made a tour of the Lancashire manufacturing towns in the summer of that year reported:

At Colne I visited eighty three dwellings selected at hazard. They were destitute of furniture, save old boxes for tables and stools, or even large stones for chairs. The beds were composed of straw or shavings, sometimes with a torn piece of carpet or packing canvas for a covering, and some without any kind of covering whatever. The food was oatmeal and water for breakfast, flour and water with a little skimmed milk for dinner: oatmeal and water again for the third supply, for those who went through the form of eating three meals a day.

I was informed in fifteen families that their children went without the “blue milk” from which the cream had been taken, on alternate days. I was an eye witness to children appeasing the craving of their stomach by the refuse of decayed vegetables in the root market.

James, despite the misery of unemployment got a job as a weaver on power looms at 1/6 per week. Soon he became an apprentice overlooker at a wage of 5/- per week and eventually an overlooker. This was not easy to achieve. The overlookers at Critchley Armstrong, the mill at which he worked, had only been drawn from two families in the village, and he encountered considerable opposition to his appointment and resistance to his efforts even after his appointment.

In 1867 at the age of 36, James was appointed Mill Manager. He held the position for fourteen years and in retrospect it was an invaluable experience for both him and the future James Nelson Ltd. It gave him the opportunity to see Amos, his son, trained in all aspects of weaving processes, which in itself proved to be important, but also it gave him an extended period of practical mill management, which few other manufacturers starting at that time had.

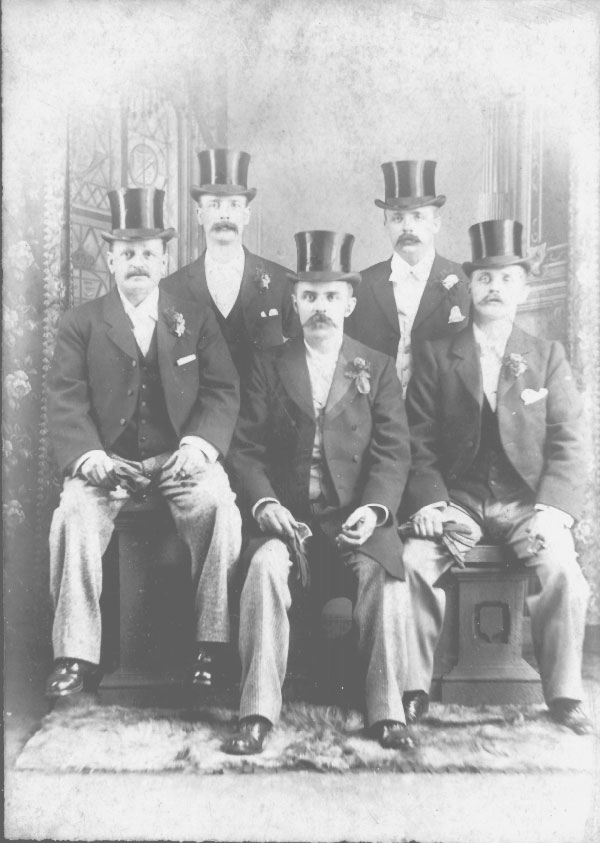

Figure 4 – Formal Group with Amos Nelson (CF) and James Eastwood on his right

James, by all accounts, was a strong willed, tough manager, but fair and highly regarded for what, I suppose today we would call his professionalism. He is said to have introduced many new methods at Critchley Armstrong, and it was typical of both him and Amos that when they came to set up on their own they did not choose the roller top looms that were in universal use at that time, but went for the more complicated cross rod looms that gave them more flexibility of production in the future. In 1881 Critchley Armstrong decided to close down the mill. James was then fifty, father to a family of six, with a little over a thousand pounds in the bank. He was however, prevented by his contract with his employers from starting his own business immediately, so he made an agreement with his son Amos and his son in law James Eastwood that they would carry on the business in their joint names until he could join them.

James and Amos had been recommended to rent accommodation in the town of Nelson. Nelson was already making a name for itself as the home of finely woven fabrics and for James it had a further advantage. The industry was beginning the period of the greatest expansion it ever knew and many small new manufacturers were starting who were not big enough to have their own mill. Some of the larger manufacturers in Nelson or indeed independent entrepreneurs had established the practice of renting “room and power” in their larger sheds to these small fledgling companies.

A further recommendation was to try and rent accommodation at Netherfield Shed, one of those mills where room and power were available. They came one Saturday afternoon in 1881, only to find that the space had been let earlier in the week. However they were told there was space in Brook Street and it was there that they rented their first premises (large enough for 160 looms), in which they installed their first 100 looms.

Amos and Jimmy Eastwood began trading as Nelson and Eastwood in 1882 at Brook Street with each being paid 35/- per week, plus it was agreed, a bonus of 5% of net profits should they both still be in James’s employment at the end of 1883. They continued until James joined them at the end of his contracted period on April 1st 1884 when the company became James Nelson. Jimmy Eastwood and later James were the “inside” men whilst from the very beginning Amos did the selling and what we would today call the commercial work. He used to recall those early days with some horror later in his life. He was just 21 when he started with no previous experience of selling, or indeed of life, outside Winewall. His fellow salesmen, travelling to and from Manchester and Bradford three times a week, were, it would seem, a fairly high living lot. It was amazing, my father used to say, how often their birthdays would come round and with what conviviality these were celebrated by all and sundry. This was not my father’s idea of selling fabric so to escape from the eternal need to drink heavily without appearing unnaturally anti social he became a life long teetotaller. The years 1880 to 1913 comprised the most extended period of prosperity that Lancashire has ever known. With a pause in 1890 when the McKenna duties halted expansion temporarily, the weaving trade doubled its 1880 production to an all time high of 8,000 million yards per annum, of which 7/8ths was exported. As the old saying went “Lancashire wove enough fabric before breakfast to clothe the home market, the rest of the day was for export”. James Nelson’s were not behind in this expansion. They moved premises several times; eventually building two very large adjoining weaving sheds at Valley Mills, which formed the headquarters of the company from 1895 onwards. By 1910 the firm’s production had increased to almost 400,000 yards per week. *They operated 24,000 doubling spindles and over 1400 looms, which increased to 2500 by 1915. By 1930 James Nelson Ltd controlled directly or indirectly 326,398 mule, 22,208 ring and 74,486 doubling spindles and 5644 looms.

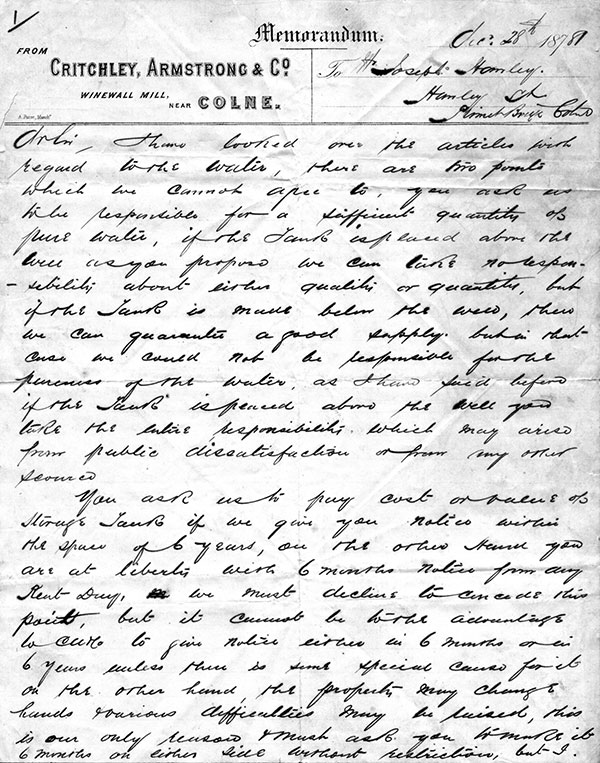

Figure 5 – Letter written by James Nelson on behalf of Critchley Armstrong

This would perhaps be an appropriate moment to analyse the reasons for the success of James Nelson’s over this period. First of all the economic climate was wholly in their favour, but even in these conditions their expansion was considered extraordinary. I suppose the next reason to advance would be that a number; perhaps a large number of their competitors were less well managed. I have already mentioned those salesmen who spent their time celebrating at the expense of selling. There were other companies, whose management methods gave Amos cause to wonder. Many never checked their supplies, either for quality or indeed quantity, and in other cases they had no reliable methods of costings. Soon after Amos began to make a name for himself he noticed that there was one manufacturer’s salesman who seemed to do little else but follow him around. When eventually he asked one of his customers what this particular salesman was doing his question was greeted with amazement. “Don’t you know” he was asked, “That chap has been following you around for weeks saying whatever Mr Nelson quoted you, I’ll take a farthing (1/4d) less”.

Figure 6 – Valley Mills showing the Sports Grounds that was built to commemorate James Nelson and the fallen of World War 1 at the top of picture. Doubling Mill on left, Lustrafil bottom right with large central block containing two weaving sheds.

It was here that James’s 14 years as a mill manager proved invaluable. To start out, as a manufacturer in those days was not difficult, looms were cheap, space and power were available to rent and with trade so buoyant capital was easy to borrow. For this reason many of the new manufacturers entering the trade, while being proficient in some aspects of it, did not have the detailed knowledge, that only experience can give, which makes bad trading years show an adequate profit and good years a small fortune. James Nelson’s was well managed. They costed their cloths and made intelligent decisions from that information. All the family watched the quality of the yarn coming into the mill like hawks. Lancashire families of that period were good at knowing where their “brass” was going to and demanding good value, but unlike many, the Nelsons never used cheap yarn of an inferior quality, believing rightly that the loss of production and the amount of reject cloth more than swallowed the advantage in the yarn price. Above all though, it was as pioneers of new cloths and processes that the Nelsons stood out from their competitors. From the moment they bought their first cross rod looms they believed in going for cloths the rest of the trade found too difficult to make, perfecting them and getting out onto another by the time the others had caught up.

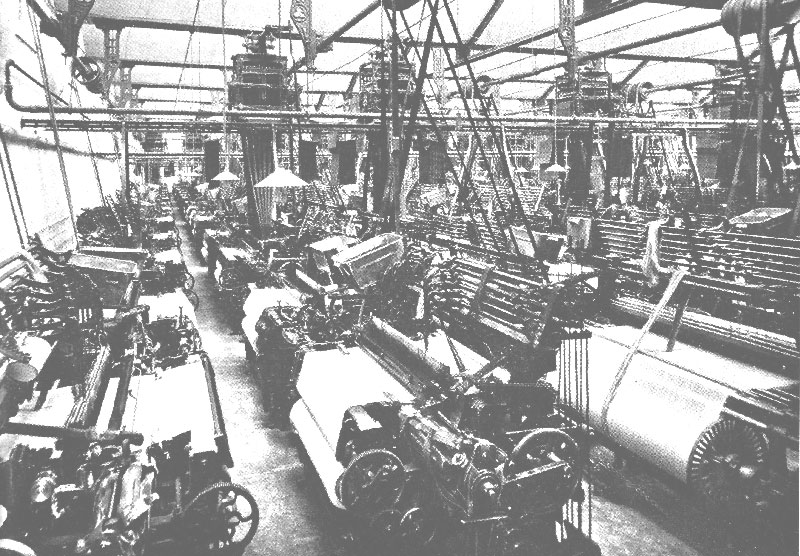

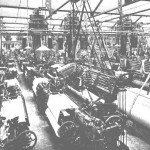

Figure 7 – Weaving Shed of Cross Rod Looms

The years we are talking about were the years before Lancashire wove anything but cotton, but even with cotton there was plenty of variety and in the right choice of variety plenty of profit.

In the early days, the trade was in weft sateens for sale to China. These are cloths with a high number of picks per inch and therefore a very low production rate. In the 1890’s though, the Nelsons saw the advents of venetians. They immediately bought the equipment necessary to make these with the advantage that not only was the profit per yard very high, because they were in great demand, but also they were low pick cloths and because of the much larger production, the profit per loom, was much higher.

This set the pattern for the future. Nelsons, paying their operatives the best wages in the area, were always looking for innovatory new fabrics and were willing to invest in them. They were constantly aiming for qualities, which allowed their operatives to earn the highest wages and the firm to make the best profit. None of these new fabrics was easy to manufacture at first, but not only James and Jim Eastwood were the practical weavers. Amos had started part time, at 8 years old, in the firm of which his father was manager, going full time at the age of ten. He subsequently worked in every department of the mill and this stood him in good stead now, for he earned a reputation, never subsequently forgotten, of being able to go down to any department in a weaving mill and work at any machine until the teething troubles of a new quality were sorted out.

Following the venetians came the repps. Again cloths with a high warp density and a low number of picks, but the weft in their case had to have 2 or even 3 yarns doubled together. James Nelsons moved into this trade early, building a doubling mill to make these yarns at Valley Mills and buying another weaving shed at Colne.

In 1909 the trade changed yet again and fine poplins, requiring this time, doubled yarn in both the warp and the weft. These developments necessitated the purchase of 2 more mills and over the next five years, two spinning mills as well.

Perhaps, more than any other cloth, Nelson’s reputation was made on the superfine poplins. Not only was the quality carefully monitored from the yarns produced within the group, but also from that bought in from outside. Joe Nelson, Amos’s eldest son, at a time when the trade was mercerising the cloth in the piece after weaving to give it extra sheen and strength, developed a machine for mercerising the warp yarn before weaving, a development that produced a much superior product to that mercerised in fabric form.

All this expansion and development, was not achieved without worries. With increasing age James had become, indeed he always had been, more conservative than Amos and one suspects that when he set out on his own back in 1881, he never suspected how far it would lead him. “Our Amos’ll ruin us yet” he was heard to say on numerous occasions and on one occasion famous in subsequent family folk lore “Our Amos has ruined us this time!”

Credit terms in those days had to be adhered to punctiliously. To go beyond the due date for payment by so much as one day, was to ensure that not only would there be no yarn for the mill the following week, but almost more importantly, the firms reputation would suffer a blow whose repercussion, as the matter was passed from mouth to mouth on “change”, could seriously damage a strong company, and destroy a weak one or one whose reserves were severely stretched.

On the occasion in question, money was very tight as usual. Payment for the suppliers depended entirely upon the prompt arrival of the principal customer’s cheque and this particular week it did not arrive. James was beside himself but despite his father’s misgivings and Will Shaw, the company secretary’s protests, Amos gave instructions that the cheques should be made out as usual, together with the accompanying’ envelopes and brought to him for signature. After he had finished his other work, Amos checked the bills, signed the cheques and posted them. For James the next few days must have seemed an eternity, (although Amos did not appear unduly worried) and his delight when the lorry from their principal supplier arrived as usual was clear for all to see. Nothing outwardly was amiss, the usual amount of yarn was delivered and it was not until he driver was about to leave and somewhat diffidently asked if he could see Mr. Nelson for a moment that there was anything remotely different. He doffed his cap, proffered an envelope to Amos and explained that there appeared to have been a mistake as he had received another supplier’s cheque in error, whom he presumed had received his. If Mr. Nelson could at his convenience correct the error his boss would be most grateful. Over the next few days all the other cheques sent to the wrong suppliers were politely returned – but by then the customers payment was safely in the bank.

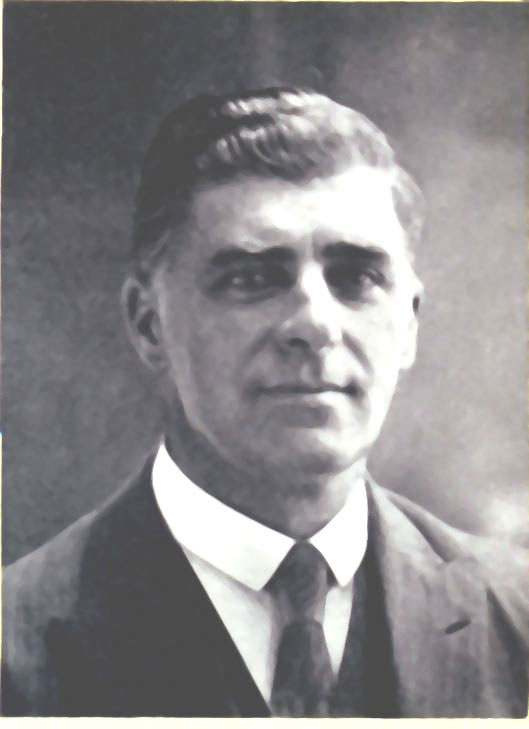

Figure 8 – Will Shaw

As the ramifications of the business grew and as this story proves, it was obvious to Sir Amos that one element in the family set up was lacking. The growing complexities and problems required someone at headquarters who could co-ordinate the finances and systems of the various companies so as to keep him au fait with what was going on. Apparently no member of his immediate family was considered suitable, nor had the necessary training. In any case this type of work did not appeal to any of them. Amos and his sons liked to manufacture cloth and sell it, all their talents were devoted fairly and squarely to this ever growing task. In this situation Sir Amos offered the job of cashier to Will Shaw in 1905, a young man of 22 who was managing clerk of their auditors and who prepared their final accounts and balance sheet speedily and to their satisfaction. He had also proved useful on many occasions in sorting out their invoices and other papers. The appointment was hotly opposed by James Nelson who said Amos must have gone mad, as no manufacture could afford to pay a dressed up clerk to look after his books. This should be done in spare time. However, Amos made the appointment and paid Will Shaw 55/- (£2.75) per week. James never reconciled himself to the presence of Will Shaw and never neglected an opportunity of saying so, much to the disappointment of Will, who was a very earnest and sensitive young man. Will Shaw’s appointment was a great success and from then onwards relieved the family of a lot of detail work, administration and financial systems, for which they had little time or inclination. Will Shaw’s appointment proved Amos right and he held it until his early death in 1941.

Figure 9 – Joe Nelson MBE

1920 marked a turning point in the history of Lancashire. While production never reached its 1913 peak, the long term or serious nature of the decline did not begin to become apparent until the slump of the 1920’s. Originally it stemmed from the fact that as a reward to India for her loyalty in fighting beside us throughout the 1914 18 war, she was allowed to start her own textile industry, protected against imports. As India had in 1913 been Britain’s largest customer, taking some 3,000 million yards of Lancashire cloth, the gravity of that blow can easily be imagined.

Figure 10 – Ralston Nelson

Never again was money easy to make in the Lancashire textile industry, other than for short periods. It had to be worked for, planned for, fought for. Successive governments refused the industry the protection that many other countries gave their own industries.

While investment in the Lancashire textile industry suffered between the wars as a result of the depressed nature of the trade and production fell to half the 1913 level, James Nelson Ltd. as it had been since 1914, invested more than ever. Their best selling cloth was a superfine poplin for the American market developed with a Manchester converter called Whitworth and Mitchell, this was registered by them as “Tricoline”, reputedly so called after an American visitor to the mill, on seeing it for the first time exclaimed “That sure is a tricky line”.

Figure 11 – Pemberton Nelson MC

But while poplins, venetian, and repps still sold, James Nelsons’, now run by Sir Amos, as he had become in 1922, and his three sons Joe, Ralston and Pemberton, anticipated that the market share would eventually be taken by artificial silk or as it later became known Rayon and cellulose acetate. Two plants were built to manufacture these yarns, one called Lustrafil in Nelson in 1923 and the other called Nelson’s Silk in Lancaster in 1927. These were revolutionary new steps for the Nelson family. Until this time they had always expanded within the range of their own textile expertise, but these two new chemical plants were both outside their practical or theoretical knowledge. Joe, Amos’s eldest son, had inherited the mantle of “Inside Man” from his grandfather James, and it was he who took on the responsibility for their success. His future son in law Tony Stansbie kept the more detailed everyday management of the Lancaster plant in the family. He ran it from its inception until the Courtaulds take over in 1963. Chris Nelson, Joe’s younger son managed Lustrafil in its early days.

More than for any previous investments however, large sums of money were required to start these plants, and large and continuing starting up losses were incurred. This was the time when other Lancashire weavers had mastered the art of weaving high-class poplins and were beginning to cut into the James Nelson market. Even Whitworth and Mitchell were now, to Amos’s fury buying fabric from other Lancashire weavers and marketing it as “Tricoline”.

This made James Nelson’s determined to control their sales outlets to a much greater degree than they had previously, and they embarked on a policy of buying or starting up Merchant Converting companies and thus getting closer to their eventual customers. This together with registering their own trade names would, they thought, prevent a recurrence of the “Tricoline” fiasco.

“Nelvo” was the name they chose for the poplin, which they marketed in the U.S.A through Clare & Heyworth, one of their new converting companies. A. T. Dyer sold a range of fashion fabrics, made in either Viscose or Acetate, under the name of “Harmony Fabrics”. Whilst William Rogerson marketed the new Moss Crepe under the name “Finest Hour” and an almost equally successful Jersey Sheer called “Entre Nous”.

In all there were at one time or another about a dozen merchant converters each specialising in its own type of fabric and its own markets. Clare & Heyworth had offices or agents in all the larger centres of population in the Colonies, South America and the Far East. C Wilkinson established stock depots for their fabrics in all the capitals of Europe and, through a local company they took over, had branches throughout Poland.

The timing of some of these acquisitions, however, proved unfortunate. When Britain went off the Gold Standard in 1930, trade with Poland proved almost impossible and the Warsaw company had to be liquidated in 1934. While the others did better than this a great deal of capital was required to get them off the ground and substantial losses were incurred with a number of them.

Figure 12 – Nelson’s Silk Mill in Lancaster – Nelson’s Acetate in the background

It seemed to be axiomatic at this time that if the subsidiary companies could fulfil their function, the supply of yarn or the selling of dyed woven production without loss, the weaving mills could be relied upon to make the profit. Unfortunately this was by no means always the case and by the early 1930’s the James Nelson Ltd. overdraft with the Manchester & County Bank stood at over one million pounds. The pressure upon the directors at this time was enormous. Joe, the company secretary Will Shaw and in the last resort Sir Amos were the ones to bear the brunt of the bank’s displeasure. Many was the time Sir Amos would arrive home with the bank manager’s instructions to “Sell that enormous mansion of yours and reduce the overdraft” ringing in his ears.

Short time was worked. At one time in 1921 the mill closed for three months, and while Amos kept the mansion, many economies were made and private possessions sold. The firm’s philosophy however remained the same and when, in the early thirties Amos returned from a trip to America full of enthusiasm for a new fabric called Moss Crepe, the seeds of another boom were laid. Moss Crepe was perhaps the most sophisticated and difficult fabric James Nelson ever produced, but it suited their philosophy exactly. It was made from both acetate and viscose rayon yarns, it used some new French twisting machinery which had been installed a year or two previously and the yarns were doubled, which could be done in the doubling mill, at that time being under-utilised. Added to these virtues were the facts that it was a difficult fabric to weave and competition would therefore be very limited, it was a low pick cloth with a high production rate and you have what I suppose could be said to have been the answer to James Nelson ‘s prayer.

Figure 13 – Nelson’s Acetate Factory in Lancaster

Thus by the advent of the 1940’s James Nelson’s was not only in the black again, it was larger than ever before within an industry which had halved in size over the past 25 years and, as never before, it was vertical, to the extent of selling finished fabric, manufactured entirely within the company, from cotton linters or wood pulp.

Its success throughout this difficult period was based, as before, on the speed with which it was able to react to market conditions, by developing and perfecting new products. This reflected the extraordinarily strong management team formed by Sir Amos and his three sons, and it is, I think, worth pausing to consider what made them such a formidable combination.

Firstly, of course, they were a very hard working family. They all got to the mill in good time, in the early years by six and never later than eight forty five even when Sir Amos was in his eighties. They arrived in time to see to the mail and talk to the salesmen before they left for Bradford or Manchester. Sir Amos always wanted to know what had been booked, what orders had been missed and why and what orders were in the offing for that day. In the early years, when they all lived in Nelson they would frequently return to the mill after supper and to the end of their lives, Saturday morning working was the rule rather than the exception.

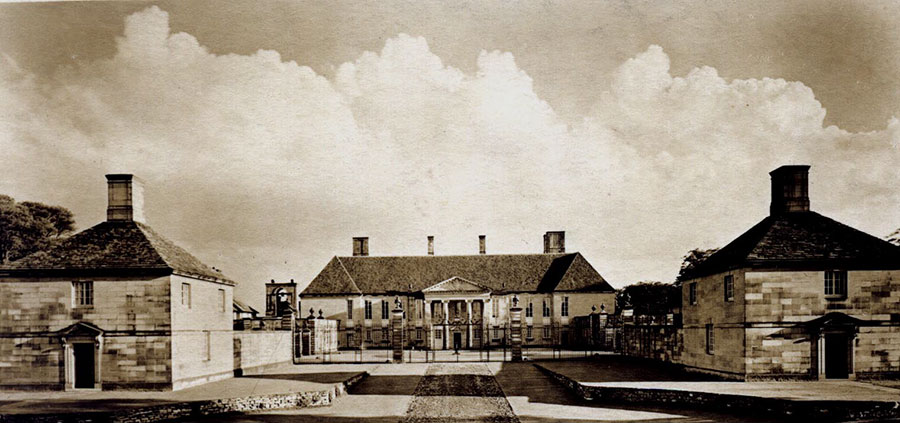

Figure 14 – Gledstone Hall ‘That enormous mansion’

There was a strict routine and division of responsibilities at the top. Sir Amos was the boss, accepted by all, Joe was the inside man, Ralston in charge of Bradford sales and Pemmy in charge of Manchester sales. These four were at the heart of all decision making. They were all at the mill together on Wednesdays and Saturday morning when difficult problems were discussed and resolved. Pemmy and Ralston saw their salesmen at lunchtime in either Bradford or Manchester and meetings were held at the mill in the evening after the salesmen returned to hammer out the problems of a production change or anything of an urgent nature.

It would be hard to over emphasise Joe’s importance to the team. He was in charge of making all the new ideas and sudden changes thought out by his father and Ralston actually happen and, by doing this so effectively over many years gave James Nelson’s the flexibility that made them so formidable. He got most of the difficult jobs the others did not like such as negotiating with the unions or with the bank manager for which his natural characteristics of doggedness and determination stood him in good stead. He was more likely to argue with his father than his brothers but remained very close to him and spent many Sunday afternoons in the country followed by tea at Gledstone. As the next two chapters demonstrate, he became a respected and influential textile negotiator and was awarded a M.B.E, in 1945.

Ralston, after his father, was the most innovative of the four. He was Amos’s staunchest ally in the family arguments. He was in fact, both staunch and loyal to all his friends and, as I have reason to remember with gratitude, his younger relatives also. As a salesman he was superb, having the good salesman’s sine qua non, a hatred of losing orders and a personal fulfilment that can only be achieved by booking them. He would frequently book orders at higher prices than his competitor due to the speed with which he reacted to an enquiry, by giving precise replies, prices, deliveries and details while other salesman had to refer back to the mill and wait for replies. Like Amos and to a lesser degree Pemmy, he certainly caused problems for the inside staff. These three took the view that while James Nelson’s prosperity was the most important factor in any decision they had to make, their customer’s prosperity came a close second. If a certain customer had ceased being able to sell a cloth where there were still large amounts to be delivered by the mill, if it was at all possible to change to another fabric that was still in demand, it would be done disregarding whatever inconvenience this posed to the production department. Amos and Ralston somewhat naturally always pushed through these changes, over the protestations of the unfortunate Joe whose task was to implement them. Ralston like his father had little time for protracted and unproductive arguments, on more than one occasion when hours of negotiating had failed to reach agreement or the settlement of a claim he is remembered to have extracted a coin from his pocket and resolved the remaining difference the with the toss.

Pemmy was a very different character, though still acknowledged as a great salesman. His approach was one of friendship. A genial, likeable individual selling to only the largest Manchester customers, he became their friend and it was through this friendship and his determination that James Nelson’s would do their utmost to further and protect their customer’s interest, that he succeeded in gaining and maintaining more than a fair share of the trade available. He it was who kept 1000 looms running with his sales of Tricoline to Whitworth and Mitchell.

Outside this magic circle, Will Shaw, the company secretary, was probably the most influential individual. He struggled, on the whole successfully, for many years to keep the financial affairs of the company in as healthy and tidy a state as was able. He had no easy task, Amos particularly was prone to regard bankers, and for that matter any bureaucrat as someone whose decision or instruction could prudently be ignored. Overdraft limits meant little to him, “send Shaw in to talk to him” was his response to the news that an irate bank manager was complaining that they had, yet again, exceeded their limit. If things got really serious, “Joe had better go and see him too”. When a bale of fabric that he urgently needed to see, arrived with a customs seal on it, not for him the aggravating wait for the customs men to come and open it, “get it open” he instructed Harry Rossall the manager in the order office, “we’ll argue about it with the customs when they arrive”. Sometimes such disregard for officialdom could lead to actual danger. Towards the end of the last war, arriving somewhat late for appointment in Liverpool, Amos found a street blocked by he police because of an unexploded bomb. “Drive on” he ordered Pickles the chauffeur, and as he would have put it, luck favoured the brave; they arrived on time albeit with some rather shaken fellow passengers.

Indeed any discussion of the success of James Nelson’s always comes back to Amos He was as much the key to the success of the company in the later years, as he had been in the early ones. Middle and indeed old age never really blunted his appetite for work or the challenge that running a company such as theirs represented. Even at the end of his life, his comment to a reporter that he could do it all again, referred not so much to his personal confidence that he would be able to, as to the fact, that given the chance he would like to. He loved business, and he loved textiles. “People who say textiles are dull as a career are talking nonsense, I love it” he replied to another interviewer. It was this enthusiasm and the sense of adventure shared that most appealed to many of his managers He inspired enormous loyalty from both his family and his work-force at all levels. In talking to people about him it is his approachability, his willingness to help, his ability to talk to anyone from a tycoon or landowner to the lowest paid operative at James Nelson’s in the same way that are most remembered. No one has ever pretended that he was less than an exacting employer. He demanded hard work, the ability and willingness to take decisions, professionalism – what an awful word but meaning a grasp of all the details and all aspects of your job and a working philosophy that put James Nelson’s and its well being very high on your list of priorities. Given that, he was fair, had a great ability to delegate and would forgive peoples’ mistakes that were honestly made, always on such occasions giving the impression that he was more interested in what could or had been done to remedy the situation than in recriminations over the mistake itself.

As a management team the four had two great qualities, the complementary nature of their talents and personalities and their loyalty and cohesiveness. While family argument took place, sometimes-heated ones, [Amos was once heard to say to Joe, then having been a mere 45 years in the firm, “When you’ve been as long as me in the industry you won’t talk such nonsense”] at the end of the day it was Amos’s decision that was final. And when that decision was once made, they all, whatever their private misgivings defended it against all criticism, just concentrating on the implementation of it as wholeheartedly as if there had been no argument. They would all have subscribed to the view that the best form of defence was attack, indeed the whole business philosophy was one of attack, trying new methods, developing new cloths, opening new markets, cutting through accepted restrictions. It was these challenges that appealed to Amos, it was his success in meeting them that kept him young until his death.