From the turn of the century, Amos took an increasing interest in political matters, first local and later national. In 1900 he was elected as a liberal to the Nelson Town Council and after only three years, the shortest period on record, he was invited to be Mayor. To be fair he was not the first choice for the post, and the Nelson Times, while applauding the eventual choice, regrets a situation where the councillor, who was the first choice, had to decline the honour because he feared the demands of the post in both time and money were beyond his means.

Figure 16 – Amos Nelson Figure 17 – Mary Driver (Amos’s first wife

Councillor Nelson had, however, created a good impression with the local press during the preceding three years. The paper talks of him as

“No orator, but a plain, outspoken gentleman who leaves one in no doubt as to where he stands”

or again

“A strong, moral character who indulges in no unnecessary platitudes.”

He served as mayor for what was then and remains still a record three consecutive years. While discussions in council were, it was frequently reported “lively”, the mayor was taken to task on more than one occasion for allowing too much freedom of discussion. But despite there being a wide spectrum of political opinion on the council, the relatively new Labour party already having ten seats, little political or personal acrimony was present.

One perhaps wonders whether a clue to his success is not given by this extract from the Colne & Nelson Times of 1906.

“Before the meeting an Wednesday, the Mayor (Alderman Nelson), hospitably entertained the councillors to dinner, and, as usual after such a function, the councillors had little to say when it came to discussing the month’s business. It has frequently been noticed that the town Council seems to lose their debating skill after partaking of any repast, quite the opposite of what might be expected. The meeting on Wednesday only took seven minutes so it can be imagined that the work of the eleven sub committees was gone through with considerable despatch”

Intoxicating liquor cannot be held responsible. Throughout my father’s time as Mayor, no alcohol was served at any function of any sort. The paper, reflecting on his three years in office, described them as “marked by ability, dignity and impartiality”.

Figure 18 – General Booth (founder of the Salvation Army) visiting Amos Nelson, a life long teetotaler in 1904

Amos described his political position at the time as that that of a moderate Liberal and when he was defeated by one vote in the Aldermanic Elections of 1905, he drew all his support from the Labour councillors. However though defeated that year, he became an Alderman the following year and a J.P. in 1907.

While his instincts were, and indeed remained for many years, those of a Liberal he was becoming increasingly concerned about the growth of textile industries in countries protected by high tariffs and their ability to export their products to Britain where there was no tariff protection. He began to voice these feelings, at a time when they were anathema to the Liberal party and were beginning to be espoused by the Conservatives.

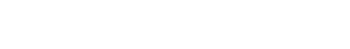

Things came to a head at the General Election of 1910. This election is now remembered as being the one caused by the House of Lords throwing out the Liberal budget and the King’s promise, not known at the time, to create enough new Liberal peers to ensure its passage should the Liberals win the election and the Lords persist in their opposition to the proposals. At the time, however, and particularly in industrial seats, tariff reform played a prominent part in the election. Amos made quite clear his views on the desirability of imposing tariffs and was instrumental in the collection of signatures to a letter which it was claimed represented 50,000 looms or some 80% of the town’s manufacturing capacity, saying they regarded tariff reforms as essential to the health of the cotton industry and the welfare of its workforce.

Denials, counter claims and accusations followed thick and fast from Liberal councillors and manufacturers. It was pointed out that any system which allowed anyone to build so large a firm as quickly as the Nelsons had done could not be so bad but more damaging was the story from America. Valley Mills at the time had over 1,000 looms weaving for the American market and the tariffs had risen so high as to threaten seriously the whole of this trade. During the course of his speeches, Amos had said that, the firm was seriously considering the possibility of moving some 300 to 400 looms over to America, as the only way they could retain a share of what had been an important market. As is the wont at election times, this had become distorted into a story that if the Liberals won the election James Nelson’s were moving their whole operation to the States. When he was not being ridiculed by his former colleagues, Amos was being painted as a man who would not scruple to leave his employees and dependants high and dry in order to make even more money than he already had by moving across the Atlantic.

The whole episode must have upset him greatly. A fortnight after the election he resigned from the council and the Colne and Nelson Times at this time more sympathic to him than its Liberal rival, The Nelson Leader, stated that,

Alderman Nelson has resigned as the attitude of his former friends and colleagues has compelled him to come to the conclusion that he cannot any longer remain connected with them in public enterprise. When you know how his statements and actions have been misunderstood or misinterpreted by the political opponents how can you be surprised in Alderman Nelson taking the course he has.

At the subsequent council meeting generous tributes were paid to him from all sides, including Councillor Tattersall, whose remarks it had been that caused his resignation. Several councillors referred not only to his public work, but also to his munificence, particularly towards the elderly in the town and Alderman Haytock called Amos

One of the most genial people to work with on a committee I have met in twenty years on the council

At the second election of that year, in December, there was again no Liberal candidate but this time Amos felt he could appear on the Conservative platform, and while commending the services to the town of the Labour candidate, stated that in his opinion the prosperity of the town could only be safeguarded by voting for tariff reform and the Conservative candidate. This effectively ended his connection with local government and in 1922 his services were rewarded by a knighthood.

Increasingly from this date Amos’s interests switched from local to national politics. He was always conscious of the drawbacks, imposed on his political performance and especially his public speaking by his lack of education. As he would frequently tell his audience, for him full time schooling ended when he was eight, grammar was never part of the curriculum and until he was 21 he never spoke anything but the Whinewall dialect. However his concern over the Free Trade as it was then practiced and his conviction of the necessity for some kind of tariff reform, not only overcame his initial diffidence, but also caused him to leave the Liberal party and become a Conservative. He remained a consistent advocate of some measure of protection for the rest of his life, writing letters both privately and for publication, speaking on platforms and fighting the 1923 General Election as a Conservative on that issue.

Tariff reform at that time was a very emotive issue. It was typical, not only of Amos but the whole campaign, that few other subjects were mentioned in his speeches and as he admitted in one of them he found himself at odds with the Liberal party on nothing but the Free Trade issue.

His remedies for the widespread unemployment prevalent throughout the country at the time were based upon withdrawing free access to this market from all countries other than the colonies and those, which offered us reciprocal free trade access into theirs. On top of this, free access would be given to all items we were unable to produce ourselves, agricultural, horticultural, whole or part manufactured. Apart from these exceptions tariffs would apply to all goods especially singled out being wines and spirits from non-Empire countries. A subsidy would be given to the farmers in order to allow them to modernize and become more efficient and a national profit sharing scheme would be introduced as soon as industry was back on its feet. In the event Nelson was won by Arthur Greenwood the Labour Candidate.

Although he lost the election, Amos lost none of his enthusiasm for his theories and became well known for them. In reply to one of his letters Philip Snowden, by then Viscount Snowden and Chancellor of the Exchequer in Ramsay MacDonald’s Labour government wrote:

Dear Sir Amos,

I thank you for your letter which I have read with interest. I am sorry to see that in spite of the experience of the last two years, which are such an overwhelming condemnation of tariffs, that you are still such an incorrigible protectionist

…………and ending……………

I do not think this letter will have any effect upon you. We must (like the cabinet) agree to, differ on this matter.

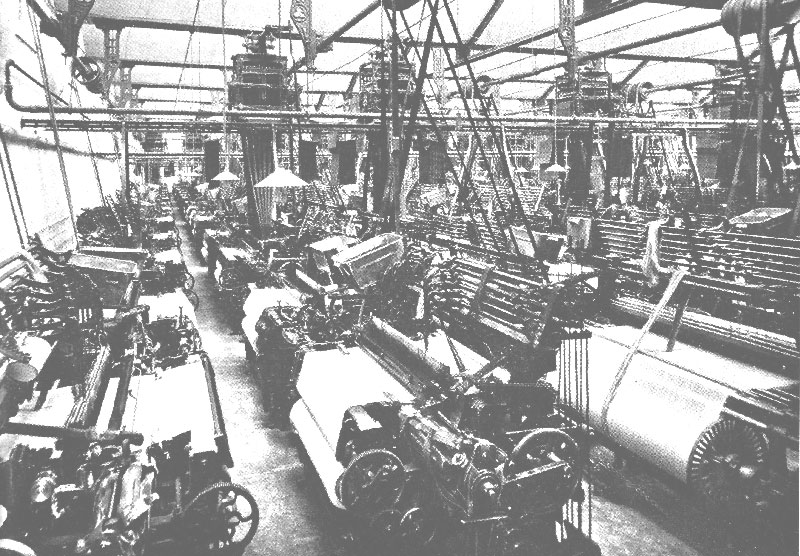

With the increasing prosperity of the firm, so the living standards of the family improved and their accommodation expanded. From small terraced houses close to the mills, they moved into progressively larger houses in other parts of Nelson. When the motorcar became a reliable method of transport they moved into the country. Amos was the first to go, buying the Thornton in Craven estate in 1912 and living there in the Manor House. In 1920 however he also bought the adjoining Gledstone Estate from Col. Roundell, the sitting member for parliament for the Skipton Division.

Figure 19 – First Page of Lord Snowden’s letter

Figure 20 – Old Gledstone

His first idea was to modernize the existing house, but changed his mind and built the new hall some half a mile away above the existing kitchen garden. The reasons for choosing the new site were twofold. It was firstly thought to be a warmer site, sheltered as it was from east and west winds, but Christopher Hussey, in his biography of Sir Edwin Lutyens gives a clue to what was probably the main reason.

Where falling ground is available, sloping into a great view, the garden designer experiences a challenge and an inspiration. He will do his best to move heaven and will certain to move a great deal of earth in order to bring a site withing his power.

Sir Edwin Lutyens then, could I think be said to have had some influence on the final choice of site.

The building itself took four years. It was started in June 1923 and Sir Amos moved into residence in September 1927. Two cottages were demolished to make way for the hall and some 200 workmen employed in its construction. These were brought in by wagon each day from all the local towns and a large canteen was erected to give them lunch and house those without other accommodation. The building created enormous local interest. As it coincided with the building of Wembley Stadium it became known locally as “Little Wembley” and reports as to its progress appeared regularly in the local press. Apart from giving employment to those actually working on the site, it brought income to numerous local contractors, quarrymen from Tubber Hill Quarries and the villagers who almost all took in lodgers at the time.

Figure 21 – Old Gledstone being demolished

Figure 22 – Gledstone Hall seen through its gates which were made by the village blacksmith Walter Hoggart

The result was, not only one of the masterpieces of twentieth century domestic architecture, but also a house that pleased Amos enormously. He referred to it always giving a happy, restful, peaceful feeling as he entered the door and being ideal as far as comfort, lighting and general arrangements were concerned. The financial arrangements however were a different matter. Let him take up that part of the story in his own words.

In November 1920, I was going to India and it happened that Sir Edwin Lutyens was going on the same steamer. My idea at that time was to make the Old Gledstone, as we call it, more up to date, and Sir Edwin had been supplied with plans by our architect, Mr Jacques. I had been told by a Mr Hemmingway of Ilkley, who had had a house built, that I must get my own architect, just to keep Sir Edwin from overspending.

The plan got out was simply magnificent, but unfortunately beyond my means altogether and we decided we would build a new Gledstone. I told Sir Edwin that the limit I wanted to spend was £40,000. I told Mr Jacques and Sir Edwin the type of front I wanted. I do not know who suggested the size of rooms but when the first plan was submitted, I thought it very good but the rooms too big. I was than told they could not build the house at anything like the price so the size was reduced considerably with the plan retained. Here again, I was told, the cost would be at least £60,000. I really did not want to spend anything like that amount. But as we were doing remarkably well at the mill at that time, I consented.

I made a proposal to the architects, that I would go even further and pay commission on £70,000 but whatever was spent less than that they would still have the full commission. We seemed to get along very well and by the time we were ready for the roof, I thought we should be able to do the houses for £40,000, but then the trouble began.

Plumbers, electricians etc. arrived; it was found that only slates from Gloucestershire would please and the money began to disappear by leaps and bounds. Every time I asked the men in charge what the cost would be, the answer seemed to be the same “you are going to have a beautiful house”. My reply was ‘what is the use of a beautiful house if you haven’t the money to live in it”.

Just at that time our old poplin trade, which had been doing well during the building period suddenly began to collapse and to complete payments on the building, nearly all my outside investments had to be sold.

James Nelson’s paid dividends until 1930, when these ceased until the mid 1940’s and by 1931 Sir Amos’s financial situation was so serious he was being pressed by his solicitor to sue the architects for damages. This he said he would on no account do, but undoubtedly his financial problems throughout the thirties were intense and resulted in a lot of pressure being brought to bear on him not only by the banks but by members of the family.

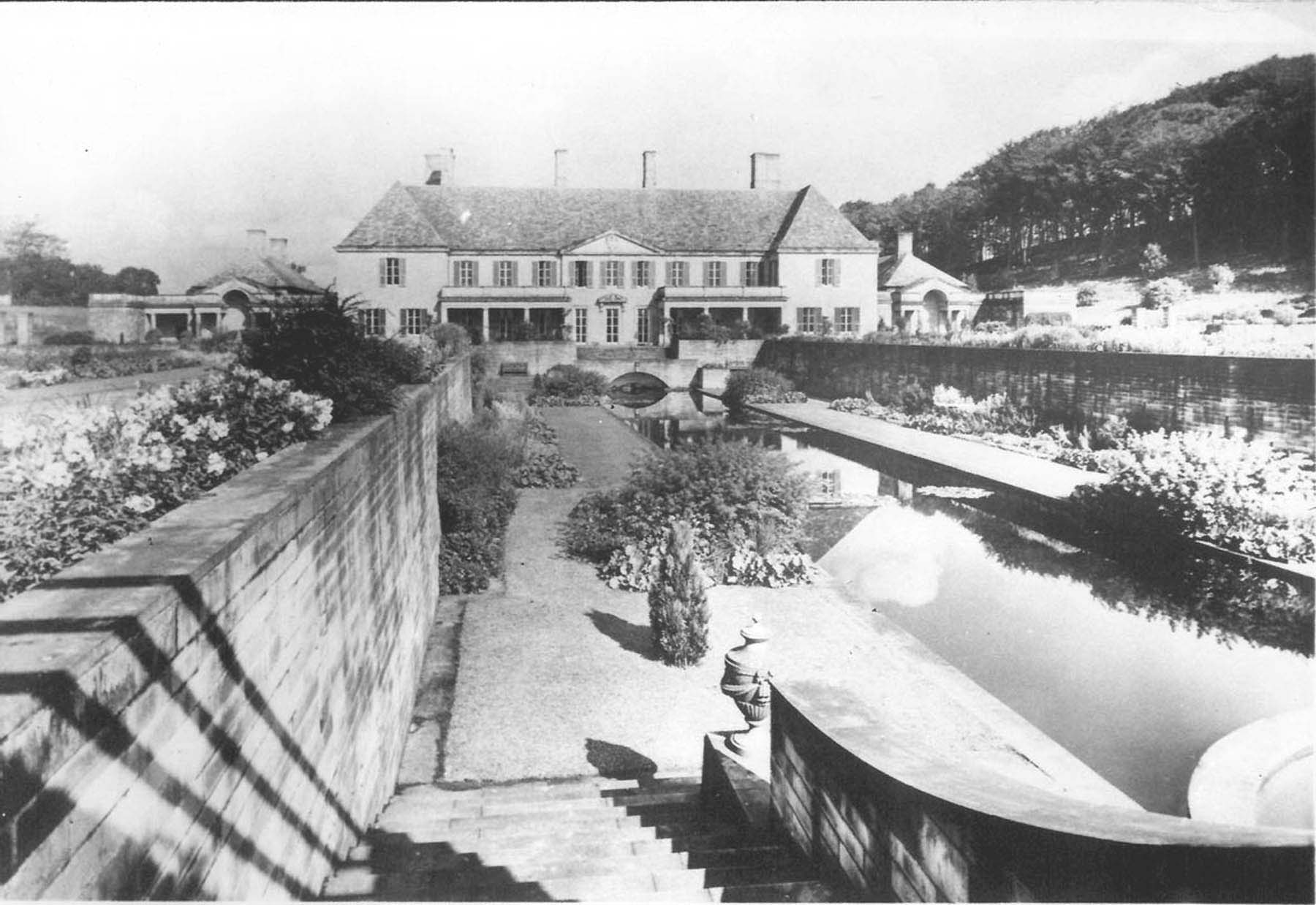

Figure 23 – Gledstone Hall Sunken Garden, the planting scheme was by Gertrude Jekyll but implemented by William Robinson, Gledstone’s Head Gardener

There were lesser embarrassments, the balance of the architects commission went unpaid for a long time and as Amos stated in one of his letters “different societies expect huge subscriptions from anyone residing in a house that size, but one has just to smile and give a guinea where probably fifteen was expected.”

Sir Amos used to say at the end at his life, that, the first time after the twenties that he ever had money to spend was after the company went public in 1946.

Despite all these problems, Amos’s relations with Sir Edwin must have remained remarkably warm as, in 1933, he asked Sir Edwin to be my Godfather. Sir Edwin replied that while he was honoured to be asked, he felt that, at his age, his days of being a Godfather were well past. And how right he was as he died nine years later, five years before my father.

Another story is told of Sir Edwin and the first Lady Nelson. During the hard times accompanying the building of Gledstone, Lady Nelson gave instructions to Mr Jaques, the architect supervising the day to day work, that he should find some cheaper substitute for the marble that was planned to go down in the hall. Jaques, somewhat naturally, reported this to Sir Edwin who wrote to Lady Nelson:

On no account can you alter any of my designs while I am in charge at Gledstone. Once the house is finished I will hand it over to you but until then my decision is final.

This obiously rankled and was remembered, because, a short time later, when the house was completed and Sir Edwin on his way to Liverpool, he wrote and asked if he could stay the night. Lady Nelson apparently replied that on no account could he come now that she was in charge, until invited by herself – and sent an invitation in the next post.

Figure 24 – Shooting Party on day before Sir Amos’s death. Sir Amos is in the centre, Ralston on Amos’s right and Chris on Ralston’s right