After the rather lengthy digressions from the story of James Nelson’s that the last three chapters have represented, it is now time to return to that, as the First World War is about to end.

For a firm which made it’s money out of innovation, it was natural that James Nelson’s should take an early interest in the development of Rayon. This coincided with Joe’s daughter Ruth, meeting a handsome young Oxford undergraduate called Tony Stansbie, who was reading Chemistry, Physics and Mathematics after serving in the First World War. After taking his degree in 1922, he started work at Valley Mills and in 1923 went to Germany where much of the development work into these new fibres was being conducted.

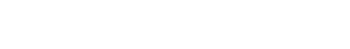

Figure 25 – Sir Amos & Lady Harriet Nelson

On his return, he went up to Durham University where research was also being carried out into the uses of cellulose. Then with three of the Ph.D’s he had met there, he came down to Lancaster to start a plant to extrude Cellulose Acetate in a yarn form which became Nelson’s Silk.

Soon after Tony joined James Nelson’s, Amos read, or was told of, a brilliant young chemist called Sydney Barker who, after taking a first in Industrial Chemistry at Manchester, had gone on to get a scholarship which allowed him to get an M.Sc. in Textile Chemistry. Amos asked to meet him, and on hearing that he was related to a certain Major Barker (who had been kind to him and his wife soon after their marriage), offered him a job as assistant to a Mr. Harrison. Harrison was at that time leading the James Nelson research team into the other cellulosic fibre, Viscose.

Unlike the Acetate plant, Viscose was going to be manufactured on the Nelson site, as usual with Joe in charge. Production got under way and progressed throughout the 20’s.

In 1931 Sydney Barker realised that if 2 rollers are set up almost but not quite parallel to each other, a rubber band, say, looped over these rollers at one end will work its way down to the other, when rollers rotate. The speed at which it does this is dependant on the angle at which the rollers stand in relation to each over. From this observation he realised that he could develop a machine which took newly formed viscose yarn straight from the bath of sulphuric acid into which it had been extruded and pass it along these rollers, stretching it, setting it, washing it and finally drying it before it was wound onto a bobbin at the other end. Thus six processes which were previously done separately could be done on one machine with no handling and with great advantages in both terms of quality and price.

The first prototype machine began to run in 1935 and by 1939 the system had been perfected with the added advantage that because of the superior quality of the yarn and the reduced potential for damage through handling, finer, silkier yarns then ever before were able to be produced. Unfortunately 1939 also brought the war and cessation of all development while all factories were turned over to war production and the manufacture of utility cloths.

By the time the war ended and Lustrafil was rebuilt, extended and equipped with the new machines, nylon had been developed in the U.S.A. and because of its strength and drip-dry qualities, effectively took much of the market in fine fabric that Lustrafil was hoping to make its own.

The Nelson process was though a great breakthrough and after patenting, was licensed to Harbens in England to produce and a licensing arrangement was made with Dobson and Barlow to produce the machines for sale all over the world. Altogether some 350 machines were built, each with 80 spindles, sold to 7 countries and netted about £500,000 to Nelson’s in royalties.

The story of the patenting was quite interesting. When Sydney Barker was explaining the principles of the machine to the patent agent he kept shaking his head and explaining that everything had been done before. Just before they left, the patent agent asked Sydney how he threaded up the machine and Sydney explained that this was done with a bit of string with a hook on it attached to a piece of elastic with an eye on it. “Ah!” the patent agent is reputed to have said, “that’s the only thing about the whole process that you can patent” but as it was the only way the machine could be threaded up it worked and was registered.

Another factor that helped the profitability of Lustrafil was the fact that Courtaulds Ltd., the largest producer of Viscose in the U.K. operated a cartel with the other spinners of the yam and rather than reduce prices in times of glut would cut their production accordingly. Lustrafil as part of one of the largest weavers in the industry was not allowed to be part of this cartel and so was allowed to cut prices by up to 10% and remain at full production when trade was bad.

The end for Lustrafil came in 1960 when a fire wiped out half the plant. Courtaulds then paid us £400,000 not to restart, which together with the £300,000 from the insurance and the £100,000 from the sale of equipment remaining was accepted.

At Lancaster, meanwhile, Tony Stansbie and his three chemists had got the plant into production. These days between the wars were not ones when there were management incentive schemes or share options, but perhaps the same end was achieved by Joe when he told Tony that he and Ruth could on no account announce their engagement until acetate had been produced at Lancaster.

During the Second World War, both these plants were closed and at the cessation of hostilities much work and money had to be spent on getting them going again. Nelson’s Silk at Lancaster had to be largely rebuilt and it was decided that the flakes of cellulose acetate that were needed to produce the yarn could only be produced on a scale much larger than Nelson’s Silk could ever use. In order to produce this quantity a tripartite agreement was formed with Erinold a British plastic extrusion company using cellulose acetate and Hercules Powder, an American company who marketed the product internationally, and Nelson’s Acetate was built, which is the only part of the company still in production to day.

Let us though, get back to the main thread of our story. For all their expertise at pioneering new cloths and processes, Amos, Joe, Ralston and Pemmy seem to have come quite late to the concept of mortality. While Joe’s sons, Gilbert and Chris and two others were put on the Board before the war, it was only the four original directors who had any real say in the running of the company or were informed or consulted about developments or decisions.

In 1946 though, they realised that in order for the company to survive their deaths or retirements, some financial reconstruction was essential and the Whitehead Industrial Trust stepped in and bought about 70% of the existing £1 shares, subdivided them into 20 x 1 shilling shares and put these on the market at 5 shillings per share with employees being given preferred status, few of them though took up the shares.

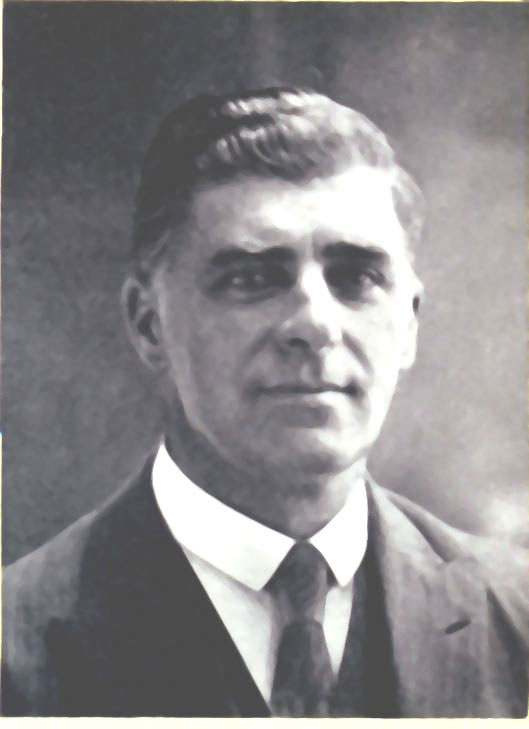

Figure 28 – 12th November 1946 Presentation to Sir Amos Nelson

Presentation dinner described by Tony Clay in a letter to his mother Some of those in our story appear; Tony and Phyllis Clay – sitting on left of picture, Sydney Barker and his wife – sitting right of picture, Jack Whitham – standing third from right, Norman Shaw – standing fifth from right, Chris and Mary Nelson – the only couple sitting inside the horseshoe, Gilbert is immediately behind them. The top table from the left: Mrs Tom Hartley, with her husband behind her, Sir Amos and Lady Nelson, (with Maud standing between them), Ralston and Pemmy.

Contents of Tony Clay’s aforementioned letter:

“We had our affair at Stirk House last night and it was most successful. There were about 50 altogether, 25 men and their wives – the only single man being H.P. Nelson. The 25 were what grandfather and DRN love to refer to as ‘the team’, ‘the key men’ or the shareholders of the late company. They were all directors, managers or undermanagers of all the companies associated with JN. We (Gilbert & Marie, Phyllis and I) got there about seven to find most people already there, with Aunt Maud playing the role of Visiting Royality to perfection. We had drinks until 7:30 then dinner. As we went into dinner we were ‘introduced’ to Sir Amos & Lady Nelson – as Jack Whitham had previously remarked to me ‘I’ve heard a lot about yon chap and I’m really looking forward to meeting him’. But of course this ceremony was for the benefit of the wives. The table was a straight U with Grandfather and Harriet in the middle of the top with Mr & Mrs Burgess on one side and Mr & Mrs Hartley on the other. Tom Hartley being the oldest employee was making the presentation and so naturally was at the top, whilst everyone else got their places out of a hat, the wives always being next to their husbands. I was next to Mrs. Alwyn Whitham and Phyllis next to our Mr Whitney who was in a really humourous mood. Opposite us were Mr & Mrs Joe Foulds. After coffee we had a photograph taken at the table and then came the speeches. Mr Heywood led off and everyone spoke except four. I was next to last with Percy Whitney last – the speeches being in order of length of service. Tom Hartley wound up and made the presentation to Grandfather and Jon Shaw a bouquet to Harriet. Grandfather, who was obviously very touched by the sincere statements about him everybody made and by the tray with everyone’s names on, said whereas most people were dead before they heard such eulogies spoken about them he considered himself very fortunate in hearing all these things while he was alive.

We all left about 11o’clock, except the D R Nelson’s, the A C Burgess’s and H P Nelson who were last seen in the bar! Uncle Pemmy was very quiet and subdued and was very nice to Phyllis. He was nowhere near us at the table. Gilbert & Marie, Mr & Mrs Smethhurst and Mr & Mrs Edwards came round to Grange Fell with us and didn’t leave until nearly 1am so it was quite a late night for us.”

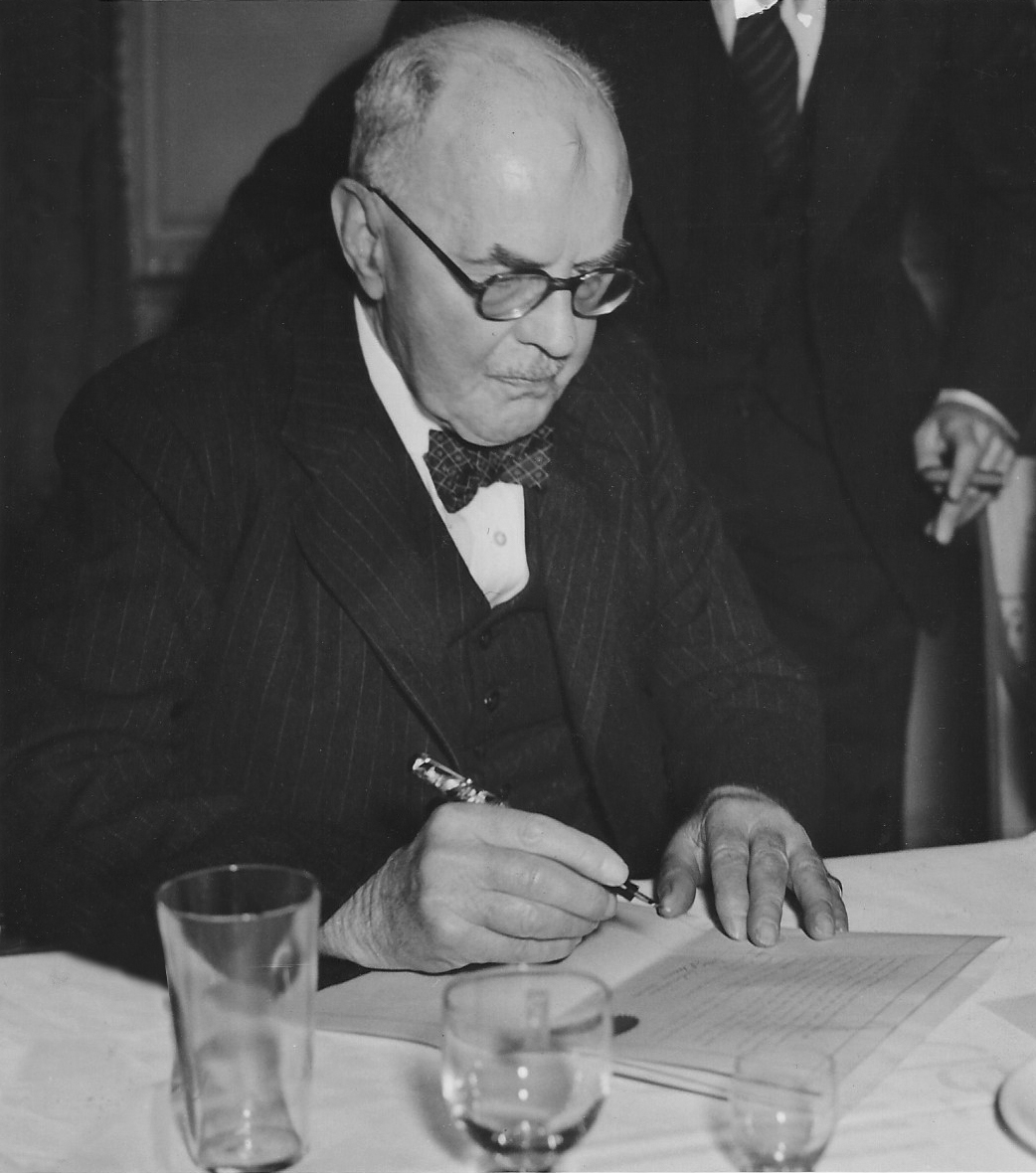

Figure 29 – Prospectus for James Nelson’s

The Nelson family received just under £3 million pounds for the shares they sold. Amos, aged 87, was given a 5 year contract ( he claimed he wanted a 15 year one) at £ 4,000 p.a. as were Ralston and Chris. Joe had died earlier in the year and Pemmy and Gilbert retired.

The first meeting of the new public company was arranged for August 14th. 1947 but had to be postponed due to the sudden death of Amos the previous day. So, within a year, from having a settled team of four, who had managed the company successfully for the last 40 years, there was only one, Ralston, left. Chris, Joe’s second son, who previously had been mostly concerned with Lustrafil, became Managing Director and Tony Clay, the son of Amos’s daughter, Hetta, and had just become a director after serving five years in the Merchant Navy, became Assistant Managing Director.

Trade remained very bouyant in those first few years after the war. Cloth sold itself and Ralston felt so able to cope with things on his own, that Chris was sent off to the States to try and find a partner with whom to erect a Viscose spinning plant and Tony was sent off to Australia with the same object. Chris’s trip was unsuccessful, but, while Tony Clay did not find a partner to develop the viscose business in Australia, James Nelson’s did, as a result of his trip, build a weaving mill in Tasmania.

At Nelson, Ralston was turning more and more to Will Shaw’s son, Norman to help him with the strategy and direction of the company. Norman’s involvement with the company can best described in his own words:

It was in November of 1931 that I qualified as a Chartered Accountant with Nelson’s auditors, Rawlinson, Hargreaves & Co., Burnley, after five years articles. This arrangement had been agreed between Will Shaw and Joe Nelson, the idea being that I should follow in father’s footsteps. However, when the end of 1931 arrived James Nelson had problems. Trade was bad and to crown all the group had acquired something like 10/12 merchant companies in Bradford and Manchester, about which they knew very little. Sir Amos and his family had no practical experience of merchant converting and had entered into this field boldly and optimistically, thinking they were going to be certain money makers. Unfortunately, this did not prove to be the case. A few companies did well, others were not so good. In any case Sir Amos stepped into the argument something on these lines. “Look here, Will Shaw’s only a young fellow, he doesn’t need any help. Send Norman to Bradford for a year to see if he can sort things out and learn the merchanting business. Afterwards he can come back to Valley Mills’’. On January 1st, 1932, I set off to Bradford and was appointed Secretary to two small subsidiary companies, salary £4 per week. ”Riches’.

In the first few weeks, Sir Amos came to Bradford and climbed three flights of steps in Bradford warehouse and took me out to lunch. I remember that lunch most vividly. Sir Amos was 71, he was absolutely immaculate and, as always, carried a walking stick. This was not my first contact with Sir Amos. In fact I have virtually known him all my life. As a small boy during the 1914/1918 war I attended Walverden School and often meandered round to Valley Mills on my way home and called in the office to see my father. The immediate inducement was to get a bar of chocolate from my father but already in my child’s mind there was something fascinating about Valley Mills. “The Mill” was a constant topic of conversation at home for both my parents. Obviously since his appointment, Will Shaw had been captivated by the Nelson family and was greatly impressed not only by Sir Amos, but also by the three sons. My mother was far less impressionable on the business side but she was closely related on the family side. in fact she was first cousin to Sir Amos, her father being brother to Mrs. James Nelson, Sir Amos’ mother. She was always known as Aunt Mary Anne. Also as a young girl my mother had learnt to weave at Valley Mills along with her four sisters. In fact there were always sixteen looms allocated to these Hartley sisters and I was always given to understand that the most profitable sorts were earmarked for these four girls. As long as the looms were kept running efficiently it didn’t seem to matter which of the girls was working. A more casual world than today. So what with the family connection and my father’s job, I was pretty well indoctrinated with the importance of the Nelson family.

On my childhood visits to the mill, Sir Amos didn’t pay much attention to me. He always said a brief word or two but there always seemed some important matter of business to be talked about and I was left in no doubt that there was no time to waste. I formed the impression that he was a rather hard task master and perhaps lacking in warmth. A few years later, actually in 1926 when I was seventeen, this early impression was modified when we met again on holiday in Llandudno. I had gone for September holidays with the family and we were staying at the Imperial Hotel. One day there was an important arrival, the hall porters were all on the alert and a large Rolls Royce produced Sir Amos and Lady Nelson, together with their daughter Constance plus luggage. The entourage received the full VIP treatment and were ushered into their suite with the greatest deference and attention. There was not a shadow of doubt that the party was held in the highest importance and consequence, much more so than would be accorded today.

The first Lady Nelson was delicate and not very mobile and spent much of her time in their suite with her daughter. Consequently Sir Amos contacted Will Shaw and asked if he had brought his golf clubs. As a matter of fact father had got his and so had I who was virtually a beginner. As a result of this the three of us played three or four times at Maisdu, the local course, and had a most enjoyable time. Sir Amos treated me as an adult and we had a most pleasant few days together. Sir Amos was 66 years old, a very steady player and could hold his own with either of us. To me a man of 66 seemed very old indeed and I was astonished at the way he tackled the rounds. He was an excellent walker, he never failed to complete a hole and although he was not a long hitter he was usually straight down the middle of the fairway. Obviously he got into a few bunkers but he always played out, even if not the first time. Sir Amos’ concentration was superb and he played to win. The three of us had a grand time and I warmed to him tremendously. Business was never mentioned, we were out for pleasure and enjoyment, no one more so than Sir Amos. As so often happens, a few rounds of golf together and one gets to know and understand each other. To me it was a very memorable few days and my heart warmed to this great and exalted man who was going to be my future boss.

For the next five years as an articled clerk I had little contact with Sir Amos. I was not allowed to go on the Nelson audit because of my father’s connection. In any event I learnt something of the James Nelson Group as I saw the final accounts from time to time and my father confided in me completely. From 1926 to 1931 was a very momentous five years. The period contained the Wall Street crisis in America in 1929 and for all these years Britain was suffering from deflation following the return to the Gold Standard in 1925. These were years when prices were falling all the time, and in textiles Manchester and Bradford merchants were able to drive very hard bargains. In fact they jolly well had to, to keep alive. At James Nelson there was maximum effort. Sir Amos was indomitable and the more difficult things became the harder he worked. His brain never relaxed, he was always looking for “something new” and the whole family backed him to the hilt. Employees at all levels showed their loyalty and affection and were petrified of losing their jobs. The dole was 10/- per week and the unemployment figures were mounting to unprecedented levels. It really was a grim time. As an articled clerk I was travelling around Lancashire and Yorkshire, auditing firms mainly in the textile trade and most of our clients were in dire straits. Will Shaw was inclined to be very pessimistic and worried himself stiff as to whether we could survive. He and Joe Nelson took on the responsibility of negotiating with the Bank, Manchester & County, and large borrowings were incurred. In fact it seemed to me that only a miracle could save the company. Funnily enough it is quite remarkable that 1 can never remember feeling worried myself. Perhaps in ones teens it is natural to be happy and resilient and although 1 felt very great sympathy for my father and the Nelson family as well as our many clients, I always felt we should muck through, and if anyone survived it would be James Nelson. Unlike so many historians who were young in the twenties and thirties, my own memories are full of happiness, pleasure and enjoyment of all kinds. My mother was always optimistic, pooh poohed father’s anxieties and was certain that everything would turn out all right.

It was during the thirties that I began to know Sir Amos really well. His second son, Ralston, who was devoted to his father, visited Bradford two or three times a week and took responsibility for the Bradford subsidiary merchant companies and gradually we built up a relationship which was very close and confidential. Although originally attached to two small companies it was obvious that some sort of order and rationalisation must be carried out both in Bradford and Manchester. In the event A.T. Dyer became the principal company in Manchester and Wm. Rogerson like-wise in Bradford. The smaller companies were gobbled up into these two main subsidiaries. Harry Smethurst was appointed Managing Director of A.T. Dyer and in 1935 I was made Managing Director of Wm. Rogerson. My senior colleague, Clifford Burgess, emigrated to London and became James Nelson’s agent for selling loom state cloth to the London wholesalers and merchants. This decision was a daring measure because for the first time we were really developing trade with their traditional customers’ main outlets. The Bradford and Manchester merchants didn’t like this at all but it was an inevitable step to take because these large London companies had close connections with the clothing trade which was growing quickly.

Round about the early thirties Sir Amos took me to lunch for a long conversation and outlined in his wonderful simple way the current position of the group. He said really the whole picture was a very simple one. The J.N. Group owed the Manchester & County Bank about £1,000,000. Joe and Will Shaw under dire threats had promised to reduce this by £1000 per week. The interest at 5% also cost about £1000 per week so that we needed to make £2000 per week to stand still. Sir Amos was quite certain that the weaving departments could make £200,000 per annum so the real problem was to stop future losses, particularly at the merchanting end. This would leave us with a profit of £100,000 per annum, for development and new machinery. Sir Amos was quite confident that this could be done. In fact with many new cloths in the pipeline we should do much better. The middle thirties saw the birth of a few new cloths which were to revolutionise our prospects. It is true to say that Sir Amos was the real innovator of these cloths. He never stopped experimenting and his flair and contacts were incredible. The three, main qualities were poult, sheer and moss crepe. A.T. Dyer’s were allocated the poult and Rogersons, who specialised in crepes, got the sheer and the moss screpe. 1 could describe in detail the origins of these three numbers but the fact remains that Sir Amos was the person responsible for their development and exploitation which completely revolutionised the Group’s profitability. At Rogersons we flogged first the sheer and then the moss crepe with great enthusiasm and our results and prestige began to improve. Harry Smethurst, who was one of the outstanding salesmen of the time flogged the poult most successfully. Fortunately the moss crepe yarns provided much needed work for the doubling mill as the two fold poplin trade was going off or becoming cut throat.

Chris & Mary Nelson

Since the days described in these reminiscences, Norman Shaw had done well in the company and was looked on first by Amos and then Ralston as a crucial member of their team and, more importantly, of any team to run the company after their departure, and as boom turned to slump and as Ralston developed lung cancer it was to Norman that he increasingly turned.

It was already becoming apparent that Chris and Tony Clay would never work smoothly together. Friction between family members was nothing new. In 1919 Ralston confided to his sister Hetta that he was thinking of leaving the company because he could no longer stand the rows he was having with his elder brother, Joe. In a family firm things were exacerbated because, even if the working partners got on well, things could be difficult between their wives, and at James Nelson things were no different, Ralston’s wife Maud and Pemmy’s wife, Ethelwyn, could not stand each other and Maud took every opportunity in any company of baiting her.

Now, a generation later the same scenario was being played out between Chris and Tony Clay, which got worse after Ralston’s retirement and death, culminating in the resignation of not only Tony but the Production Director, Jack Whitham and the resignation from the main Board of Norman Shaw as well. At a Board meeting on the 5th. of May 1953 there was a majority of 5 to 4 for accepting Tony’s resignation and, after he had left the meeting, a vote of 4 to 4 for accepting Jack Whitham’s, with Chris using his casting vote to accept after Jack had reiterated he would be leaving the company if Tony left. Tony Stansbie now became the Group Managing Director and Harry Smethurst the Sales Director.

Figure 30 – Ralston & Maud Nelson

The next few years were lean ones for James Nelson’s. When I joined the company in 1956 the shares had dropped to 7d. per share, less than 10% of the price they had been in 1951 and it was not until 1959 that they began to climb. The trouble in those years was easy to see. James Nelson had always been a company whose success depended upon the weaving. As Amos had explained to Norman Shaw so many years before, as long as the spinning and the converting did not lose too much, the weaving mills, when they were run by Amos and his sons could make all the money they needed. Now things were radically different. Chris had been brought up at Lustrafil and was not a weaver. Tony Stansbie had always been at Lancaster looking after Nelson’s Silk, Harry Smethurst, the Sales Director had always been in Manchester selling finished cloth. Indeed there was no Production Director as such and the weaving mills were more and more regarded as providing a market and a service for the spinning mills, exactly the opposite of what had traditionally been the case. In a town where high wages had traditionally been paid and for a firm that traditionally paid the highest wages in the town, this was, however an increasingly impossible role to fulfil.

Figure 31 – Tony & Ruth Stansbie

In 1959 two things of some moment happened to James Nelson’s. The first was the Cotton Board reorganization scheme announced by the MacMillan government. Under this the government would pay any company that scrapped looms a fixed amount per loom. They could then leave the industry and many did. If however a firm wanted to modernise, the government would also pay an amount for every new modern loom that was installed. The first part of the problem was relatively easy, James Nelson’s knew which looms it wanted to scrap, made the decision, shut two of its mills and took the money. The other decision seemed harder, but it was in fact simplicity itself to take the first step, as you only, in the first instance, had to apply to buy looms by a certain date; you did not, in order to qualify for the re equipment grant, have to commit yourself to the looms until much later.

By this time Edward Nelson, John Stansbie and I were all working at the company. I was not a director, merely one of our Manchester salesmen. However I was very friendly with the Company Secretary, Jo Scott, and used to spend some time with him most evenings after my return to the mill. On this particular Friday night I remember going in to see him and and facing the rhetorical question ‘Well so we’re not going to re equip then”” I asked him what he meant and he told me that the deadline for applications for the grant was mid day the next day (a Saturday) and we had made no applications nor had any plans to do so. Well the telephones were hot and we did eventually send a driver off to the Cotton Board offices in time for the noon deadline. We later re equipped on a large scale and improved our performance as a result.

The other thing that happened in 1959 was the arrival in the firm of Joseph Seidler, or Pepe as he was known. Pepe had left Czechoslovakia in 1937, just before the Germans arrived, had worked in England during the war and after the war taken the money he had saved back to Czechoslovakia and started his company up again. The communists arrived and out came Pepe yet again with virtually nothing. By 1959 he was the co owner of a small manufacturer called Hilldrop Weaving, who foresaw the problems lying ahead for the industry, closed his mill under the reorganisation scheme and joined James Nelson’s. Pepe brought a feeling of the old days back to the mill. His methods were somewhat different; on one trip on which I accompanied him, he insisted on bringing a large case. When we arrived at the customer’s he threw open the case with a flourish, displaying a collection of the most beautiful silks and woollens and told our surprised customer to choose one which we, James Nelson’s, would reproduce so well in acetate that the customer would not be able to tell the difference. On being asked if the customer could keep a pattern of the cloth to compare, Pepe proved somewhat evasive and I seem to remember that this particular exercise resulted in a plethora of angry letters and threats of claims but never mind, James Nelson had once again someone experienced in the marketing of textiles.

Marketing in those days of the early 60’s was nothing like the sophisticated exercise it had been 50 years earlier. Now it depended on the amount of money the fibre producers were prepared to spend to advertise their products, making sure you were well enough in with those producers to get your share of the yam available and making sure you were making the right cloths and charging the right prices to maximise your profit. In this we were increasingly successful and our shares rose slowly from seven pence in 1959 to 3/4d in 1961.

There they stuck for a while. The mini boom which followed the re organisation scheme had petered out, but our profits remained reasonably healthy with all the parts of the company contributing something until 1963. In 1963 ICI Ltd. launched a take over bid for Courtaulds. These were the two largest manufacturers of synthetic yam in the country who had co operated reasonably well until this moment. ICI announced however that the future of the textile industry was so parlous it could only be tackled by the most drastic rationalisation and in its view this should start with the merging of the fibre producers after which the problems of the rest of the trade could be tackled. Courtaulds, unsurprisingly, did not agree with this scenario and, whipped on by their Vice Chairman, Frank Kearton, mounted a spirited and ultimately successful defence. Both companies though, when they emerged from their battle, were equally convinced of the necessity to rationalise the industry only differing on the methods and the roles they would each play in the process.

At James Nelson’s we had not, of course, been unaware of these goings on, in fact we had had some informal talks with Carrington and Dewhirsts, with us and Samuel Courtaulds the largest filament weavers in the trade. Both companies were aware of the need to do something, but like many things in life, we both felt it could wait till tomorrow in this case it couldn’t. On Friday November 1st. 1963 Harry Smethurst, our Joint Managing Director, – I was by this time the Sales Director – was rung up by one of our London customers, Joe Hyman, who suggested we would make a great team together and should consider an amalgamation immediately. Harry, I remember, and most of the rest of the Board thought it was a joke at first, but Joe rang again making it clear it was not a joke and the amalgamation should take the form of a take over by Hyman of James Nelson’s. This to Harry appeared even more ludicrous than an amalgamation and Harry, I remember, asking him what he was going to do for money. “You leave the money to me Harry” was his somewhat enigmatic reply, clarified the next morning when we read that ICI had lent him 10 million pounds to commence a restructuring of the Lancashire Textile Industry.

Figure 31 – Tony & Ruth Stansbie

From there events moved quickly. Harry Smethurst approached Courtaulds to offer them a minority interest that afternoon and the next day we were told that Courtaulds were not interested in a minority interest but were interested in taking us over entirely at a price of 4/6d a share. This seemed to us marginally better than the Hyman bid but not what we wanted, so that evening two of our directors travelled down to London for a meeting with a merchant bank and Carringtons again to restart the original negotiations.

Carringtons were an extremely important customer of ICI and the two of us managed to persuade ICI “To call off their hound” in the form of Joe Hyman. Courtaulds, though, had the bit between their teeth by this time, were insistent they intended to go ahead and upped their offer to 5/ a share. The next day, the 8th. November brought further meetings In London.

At a meeting with the banks, Carringtons and ICI’s representative, an amalgamation was agreed valuing the James Nelson shares at 5/6, This we thought would do the trick, value James Nelson at a fair price and ensure we linked up with a company with whom we were very friendly and where we felt an amalgamation would be of most benefit.

Not surprisingly, perhaps, Courtaulds did not see it this way, but had become convinced of the value of James Nelson to them, upped their offer again to 6/3 and at that price, equal to the highest it had ever been, we became part of what was at that time the mighty Courtaulds empire.

During the take over there had been the usual assurances that James Nelson’s would remain an independent company and a Courtaulds main board director, George Samuel, was put onto the Nelson’s board together with Ivan Hill, the Chairman of Samuel Courtaulds, their weaving division and a Mr. Hunter, Chairman of British Celanese who spun all their Acetate and Tricel. Whether he intended to be or not, George Samuel was no match for the political machinations of these two and in what seemed an indecently short time, James Nelson’s was dismembered, the spinning being managed from the Celanese headquarters in Derby and the weaving from Braintree in Essex to which I repaired as head of all Courtaulds grey cloth sales.

Courtaulds, though, proved no better at halting the decline of the Lancashire textile industry than anyone else. The Doubling mill was the first Nelson mill to close, followed by Carr Manufacturing and Nelson’s Silk. In 1981 Valley Mills itself closed for the last time and just one hundred years after Amos and Jimmy Eastwood had set off for Nelson with such high hopes, the James Nelson story finally ended.